One hundred years ago, on July 18, 1925, a failed revolutionary in a Bavarian prison cell published his worldview. Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf—half autobiography, half ideological blueprint is published—becoming one of the most influential and deadly documents of the 20th century. It outlined the extermination of Jews, the conquest of Eastern Europe, and the rebirth of Germany through racial purity and political violence and what will become the Third Reich.

At first, the world didn’t take him seriously. That was the first mistake.

Written during a brief prison sentence, after Hitler’s failed Beer Hall Putsch in 1923, Mein Kampf laid out his worldview in chilling detail. Jews were the eternal enemy. Marxism was a Jewish plot. Democracy was a tool of decay. Lebensraum—living space—had to be seized in the East. Germany’s rebirth required not only purification, but war.

At the time, few Germans read it. Fewer took it seriously. But when Hitler rose to power in 1933, Mein Kampf became a sacred text of the Nazi state. Newlyweds received it as a gift. Soldiers carried it in their packs. Teachers used it in classrooms. Hitler made a fortune from Mein Kampf. Not only did he excuse himself from paying tax, after he became Chancellor the German state bought millions of copies. By 1945, over 12 million copies had been distributed in Germany alone. The Holocaust did not come out of nowhere. It was printed, published, and footnoted—well in advance.

Outside Germany, Mein Kampf was quickly translated. Some presented it as a warning. Others sold it as a curiosity. Either way, the message was diluted—and the urgency ignored. This sanitization contributed to the normalization and gradual spread of antisemitic ideas outside Germany, as the true extremity of Hitler’s hatred was obscured, allowing antisemitism to seep into mainstream discourse with less resistance and warning.

Its English-language translations tell their own story of delay, distortion, and denial. The first version, published in 1933—seven years after its German release—was an abridgment, stripped of much of its venom, most likely censored with Nazi approval. James Vincent Murphy, the translator's identity was concealed, and it wasn’t until 1939, on the eve of war, that unabridged editions by Houghton Mifflin in the U.S. and by Hutchinson in the U.K appeared in Britain and America—too late to awaken the public. By the time the full text arrived, Hitler’s vision was already being realized in blood and fire.

Even in the U.S., the book found fans. Father Charles Coughlin, the infamous pro-fascist priest, praised Nazi ideology. American isolationists dismissed Hitler as Europe’s problem. Few understood the global implications—until it was too late. And even then, the book endured.

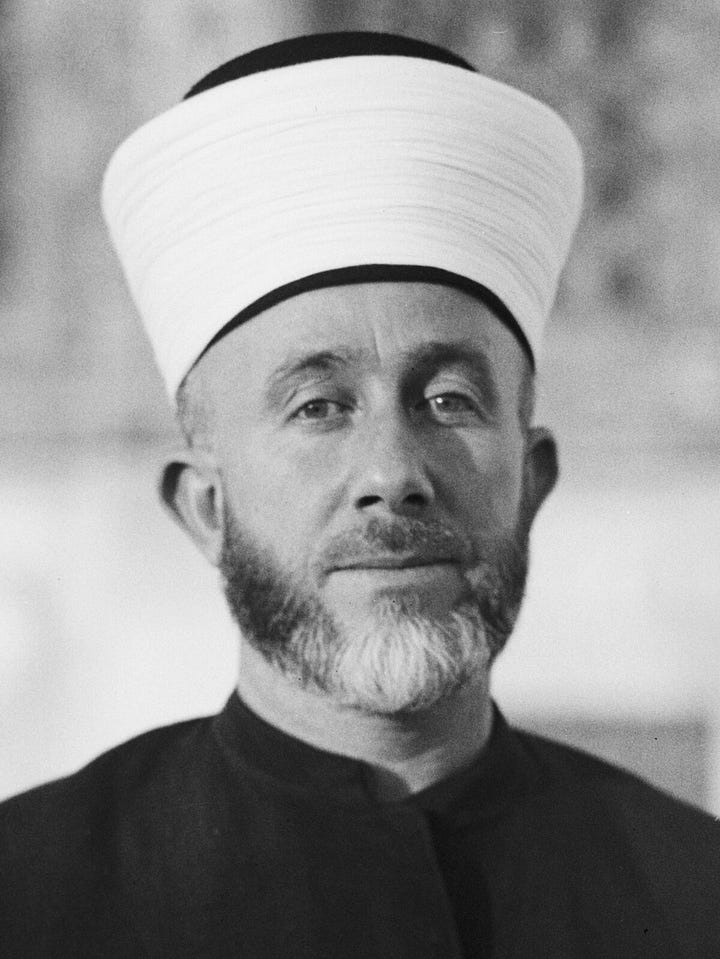

One of the most overlooked aspects of Mein Kampf’s legacy is its afterlife in the Arab and Muslim world. It was not just read—it was repurposed. Ahmed Huber, a Swiss Nazi convert to Islam, helped facilitate the translation and distribution of Mein Kampf in Arabic. He had close ties to radical Islamist networks and to Haj Amin al-Husseini—the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem and one of Hitler’s most loyal allies in the Middle East.

Haj Amin al-Husseini wasn’t a passive supporter. He met with Hitler personally. He recruited Muslims for the SS. He spread antisemitic propaganda across the Arab world. His influence helped frame Nazi ideology as an Islamic cause. And in most places, it stuck. Hitler and Himmler themselves admired aspects of Islam—particularly its perceived martial discipline, intolerance of weakness, and promise of obedience.

Himmler reportedly said he preferred Islam over Christianity, which he saw as too soft. Hitler called Islam a “religion of men,” lamenting that it hadn’t conquered Europe centuries earlier. This ideological admiration strengthened Nazi collaboration with Islamist leaders. Over the decades, Mein Kampf has been sold in Arabic translation across the Arab world—and remains a bestseller today.

In Japan, Mein Kampf found admirers among the militarist elite—not because of its antisemitic content, which held little local relevance, but because of its unapologetic embrace of authoritarianism, racial hierarchy, and national expansion. It resonated with Japan’s own imperial ambitions and the ideology of the ruling class, who saw parallels between Hitler’s vision and their own pursuit of a militarized, emperor-centric state.

In Latin America, Nazi propaganda made inroads particularly among ethnic German communities, most notably in Argentina and Brazil. These communities received German-language newspapers, radio broadcasts, and literature—Mein Kampf included—circulated through Nazi-sponsored cultural organizations. While mainstream society largely rejected Nazism, these pockets served as ideological outposts, helping to normalize Hitler’s worldview far beyond Europe’s borders.

After World War II, Germany banned Mein Kampf. But when its copyright expired in 2016, an annotated scholarly edition was released. Germany saw an overwhelming number of sales. It sold over 85,000 copies in its first year.

Elsewhere, the book never went out of print. Today, it circulates freely online—in dozens of languages. White supremacists, jihadists, and radical antisemites all find common cause in its pages. Hitler no longer needs a publisher. He has the internet. In 2014, digital ebooks became best sellers in the UK.

But Hitler didn’t invent antisemitism—he weaponized a hatred that was already global. For centuries, Jews had been persecuted across Europe through expulsions, blood libels, pogroms, and church-led demonization. In the 19th century, antisemitism became political, later amplified with fabricated texts like The Protocols of the Elders of Zion fueling conspiracy theories of Jewish control.

In the Islamic world, Jews lived under dhimmi status—tolerated but degraded—and faced massacres in places like Morocco, Libya, and Iraq. By the 20th century, European antisemitic propaganda had taken root across the Middle East. In the U.S., Jews faced quotas, exclusion, and suspicion. Mein Kampf didn’t create these currents—it distilled and amplified them into a murderous doctrine millions were ready to accept.

A hundred years later, Mein Kampf has outlived its author, his regime, and even the war he launched. It has been translated, repackaged, and reimagined—not just by white supremacists, but by Islamist radicals, political activists, TikTok influencers, and even United Nations bureaucrats. Its language has changed. Its message has not. Today, we are watching that ideology return. It speaks a new language. It flies a different flag. But it targets the same people, with the same justifications.

The result today, things like Candace Owens' insane rant calling Israel "THE MASTER OF THE UNIVERSE" & an "OCCULT NATION!" "This is a state that has a hexagram as their flag! Everything they're involved in is occult. And that's why we have to wake the world up to this very quickly."

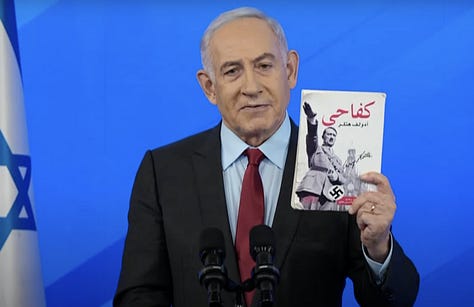

Just like Mein Kampf, Hamas wrote its genocidal charter, calling for the eradication of Jews and Israel and in September 2021, Hamas sponsored a conference titled “Promise of the Hereafter”—a strategic vision for the phase following what they call the “liberation of Palestine” and the “disappearance” of Israel. Sponsored by Hamas leader Yahya Al-Sinwar and attended by senior Hamas and Palestinian officials, the conference detailed explicit plans for governance, law, economy, and security once Israel ceases to exist

The Promise of the Hereafter Conference, held under Hamas leader Yahya Al-Sinwar, outlined a comprehensive post-liberation plan for Palestine to be implemented after Israel ceases to exist. It included drafting a declaration of independence modeled on the Pact of ‘Umar, preparations for judicial, legislative, and financial transitions, and the establishment of an interim government. Most chillingly, the conference detailed protocols for dealing with Jews post-liberation—classifying them as fighters “to be killed,” others to be prosecuted, and “peaceful” individuals who would be barred from leaving. Jewish professionals in fields like medicine, engineering, and defense would be forcibly retained to prevent a “brain drain.” The plan also called for compiling global lists of “occupation agents,” both Jewish and non-Jewish, to facilitate purges across Palestine and the broader Islamic world.

Shockingly, this genocidal framework was paired with a sophisticated diplomatic strategy. Hamas envisioned holding a major summit in Jerusalem with international ambassadors to present the new Palestinian state as a responsible actor committed to cooperation. It would notify the UN that Palestine is the legal successor to Israel under the 1978 Vienna Convention on State Succession, and a legal committee would review all of Israel’s treaties to determine which to uphold or reject. Officials described the campaign not merely as a war, but as an apocalyptic, divinely ordained “battle of the End of Days” to annihilate the “occupation entity” in a single stroke. These detailed plans expose a modern iteration of Hitler’s genocidal blueprint—repackaged in Islamist rhetoric, regional ambition, and legal-political theater, but driven by the same core aim: the total elimination of a people and their state.

Two years later, on October 7, 2023, Hamas launched a brutal and unprecedented attack—the first overt attempt to accelerate their long-stated goal of Israel’s destruction. This was no spontaneous eruption of violence. It was a direct implementation of the strategies and mindset outlined years earlier in the Promise of the Hereafter conference. The attack, marked by mass killings, kidnappings, and terror, was only the opening salvo in a campaign Hamas intends to continue relentlessly until their declared objective is achieved.

Since Hamas’ massacre, Nazi imagery has resurfaced worldwide: swastikas at rallies, graffiti honoring Hitler, social media flooding with Nazi glorification and revisionism history portraying Hitler in a good light. Even in schools in America children are exposed to drawings of Adolf Hitler.

The problem isn’t that Mein Kampf still exists. The problem is that it’s being implemented again—without the mustache. And once again, the world shrugs. Because the line between “Never Again” and “Again, Justified” is not a red line anymore. The danger today is no longer abstract. It is being openly planned and rehearsed.

The most dangerous thing about Mein Kampf was not how many people agreed with it. It was how many dismissed it. Mein Kampf was not obscure. It was not vague. It laid out, step by step, how the world could be cleansed of Jews and rebuilt through violence. The world refused to believe it. When he implemented the world looked away. Millions died as a result.

Iran’s and Hamas’ plans are not hidden in secret—they are documented, public, and chillingly clear. The October 7th massacre was a first test of the methods cultivating for years. And they will not stop. The United Nations will not rest in its inquisition against Israel and countries targeting it and failing to protect its own Jewish populations don’t show signs of changing course. Modern day antisemites are just as proud as Hitler for targeting Jews.

Mein Kampf may be a century old, but its spirit is alive in conference halls, policy documents, and the grim plans of those who openly dream of erasing the Jewish people.

This is the world we must confront. Because forgetting history and ignoring the warning signs is not just dangerous—it is deadly.