A Nation of Victims—But Not All Saints: Polish Suffering Does Not Erase Its Crimes

Polish Antisemitism Before, During, and After the Holocaust

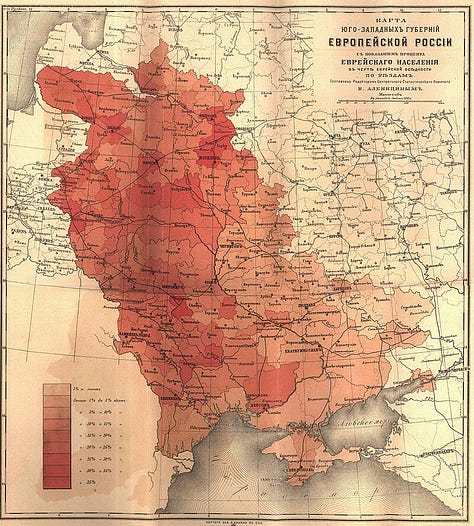

Before Poland was a battlefield, it was a home. For centuries, Jews found refuge in Polish lands—first invited by kings, later protected by charters that allowed them to live, pray, and trade. By the 16th century, Poland had become the heart of the Jewish world, home to the largest Jewish population on earth. Yiddish theater, Hebrew schools, Hasidic courts, and secular newspapers flourished from Kraków to Lublin.

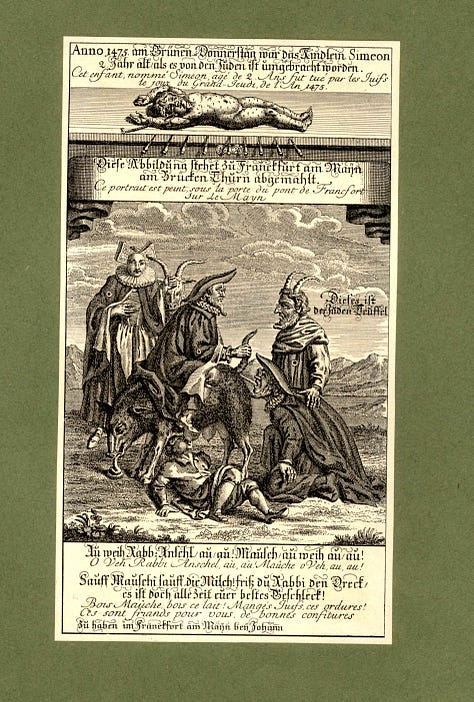

But paradise has a long shadow. Even in those early years, Jews were cast as scapegoats—blamed for plagues, accused of ritual murder, and taxed beyond reason. In 1598, Jews in Lublin were tortured and executed after a false blood libel. In towns like Sandomierz and Poznań, such hysteria was often stoked from church pulpits. Today, Sandomierz’s cathedral displays an 18th-century mural of Jews murdering a Christian child. Even in a kingdom praised for its tolerance, antisemitism ran deep—in sermons, in law, and in the streets.

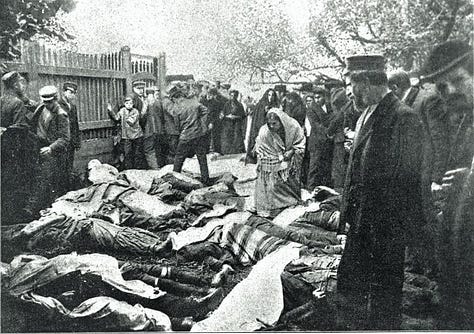

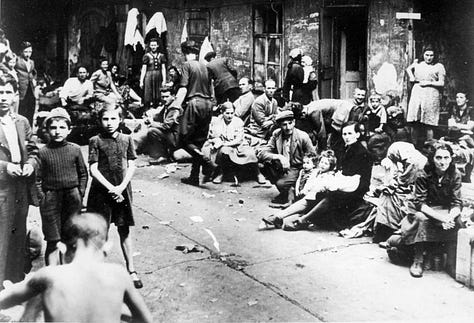

When Poland was partitioned in the late 18th century—swallowed by the Russian, Prussian, and Austrian empires—Jewish life grew harder still. Russian czars confined Jews to the Pale of Settlement. Pogroms erupted regularly. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, antisemitic riots swept Polish cities—Białystok in 1906, with nearly 100 Jews murdered; Throughout the 1930s, interwar Poland saw a surge of antisemitic riots and attacks: Przytyk in 1936, with Jewish shops destroyed and families driven into exile. In Brisk (Brześć) in 1937, Jews were beaten and businesses destroyed; in Mińsk Mazowiecki, a pogrom in 1936 led to mass arrests and serious injuries. In Częstochowa in 1937, mobs vandalized Jewish homes and shops; Kraków, Lwów, Wilno, and Warsaw witnessed repeated street assaults, synagogue desecrations, and organized boycotts. The violence was often incited or tolerated by right-wing parties and local authorities, as antisemitism became normalized in Polish politics and public life.

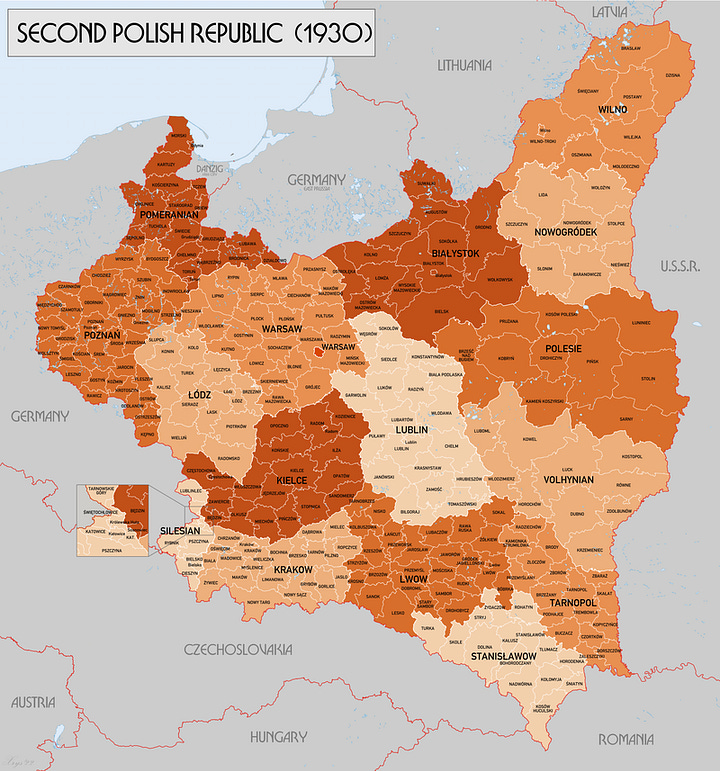

After Poland regained its independence in 1918, the violence didn’t stop—it got institutionalized. Nationalist parties like Endecja, founded by Roman Dmowski, made antisemitism a plank of national identity. Polish universities adopted “ghetto benches,” forcing Jewish students to sit apart. Synagogues were desecrated, businesses boycotted, and Jewish children attacked in the streets—sometimes with the blessing of local priests. The climate of fear, persecution and physical insecurity affected the daily lives of millions of Jews across the Second Polish Republic.

In 1937, the Polish government passed laws banning kosher slaughter—targeting Jews, a law that was reaffirmed in 2013. And increasingly, calls to create a Judenrein Poland grew louder. Parliamentarians and bishops alike demanded that Jews be expelled, not merely marginalized. The Polish government even explored the forced transfer of Jews to Madagascar before Hitler did. These were not whispered fantasies. They were campaign promises—backed, by the late 1930s, by the majority of the population.

Long before the Nazis formalized their Madagascar Plan, the idea of removing Jews to the island had circulated among European antisemites—from German nationalist Paul de Lagarde in the 1880s to French colonial officials in the early 20th century. But it was Poland, in 1937, that became the first country to officially explore the idea at the state level. Backed by government support and antisemitic pressure to reduce the Jewish population, a Polish delegation—including some Jewish experts, though the effort was not theirs—was sent to Madagascar to assess its feasibility as a mass deportation site.

While Britain had entertained territorial schemes like the 1904 Uganda Plan, and later monitored Nazi plans, it never pursued Madagascar as policy. The Polish initiative, however, directly influenced Nazi thinking, and by 1940, the Germans revived the plan as a possible “solution” before turning to genocide. What began as fringe fantasy in Europe became official Polish policy—one that imagined not Jewish integration, but Jewish removal.

According to polling and political party records, at least 60 to 70 percent of Poles supported nationalist or Catholic movements that espoused some form of antisemitism. Among university students, support for segregated seating for Jews reached over 80 percent in some institutions. The idea of a Poland without Jews wasn’t fringe. It was mainstream. The Polish government, especially from the mid-1930s onward, actively encouraged Jewish emigration, including Palestine, as a solution to what was called the "Jewish problem" in Poland. This policy aligned with the antisemitic nationalist agenda that sought to reduce the Jewish population in Poland before WWII.

Then came the war.

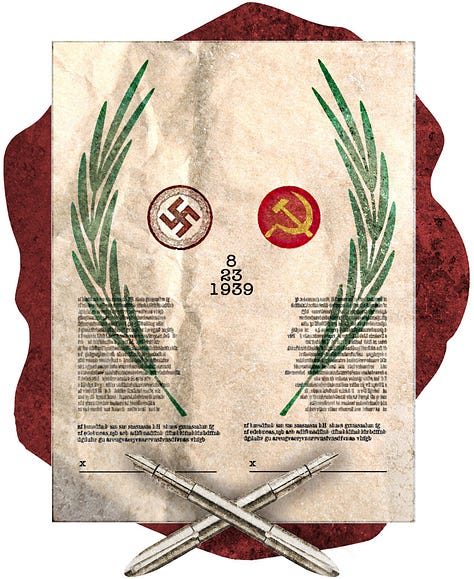

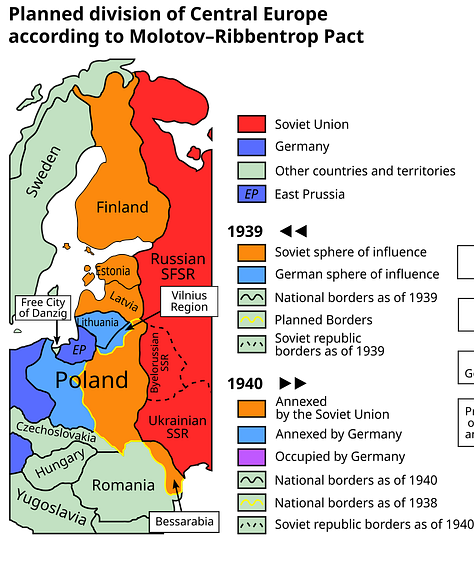

Polish suffering under the Nazis was also real—and horrifying. Poland was the first country to be carved apart by Hitler and Stalin in their secret pact. It was the only occupied nation whose entire intelligentsia—professors, priests, doctors, judges—was deliberately targeted.

Auschwitz was built on Polish soil not only to murder Jews, but to terrorize Poles. At least 1.1 million Jews were killed in Auschwitz. Other victims included between 70,000 and 75,000 Poles, 21,000 Roma, and about 15,000 Soviet prisoners of war. Millions were deported to forced labor camps. Hundreds of thousands were executed. In Warsaw alone, over 200,000 civilians were killed during the 1944 uprising—slaughtered after the Allies encouraged rebellion, then watched the Soviets wait across the river. The Nazis viewed Poles and other Slavs as inferior, and slated them for subjugation, forced labor, and sometimes death. 3 million non-Jewish poles died during the war, about half due to Nazi persecution.

The Soviets, too, brutalized Poland. In 1940, the NKVD murdered over 20,000 Polish officers in the Katyn Forest. Hundreds of thousands of Poles, Jews and non Jews—intellectuals, peasants, entire families—were deported to Siberia and Central Asia, many never to return. Polish culture was crushed from both sides. Its sovereignty erased. Its people brutalized.

But none of that suffering negates the fact that Polish society was steeped in antisemitism before the war. Victimhood does not equal innocence in this fact. When Hitler invaded in 1939, he didn’t have to build antisemitism in Poland. He stepped into a country that had already normalized it. And yet, the postwar Polish narrative—one that frames the nation solely as Hitler’s first victim—conveniently omits this history. It skips over the fact that when the Germans arrived, many Poles greeted them not with fear, but with hope: hope that the “Jewish problem” might be solved once and for all. Collaboration did not require a Polish Vichy or Quisling. It happened in village squares, back alleys, and quiet betrayals—where neighbors turned on neighbors for property, for reward, or for hate. In 2019 the Polish government chose to honor its Nazi collaborators, showing how little Poland learned from WWII.

Attacks against Jews by locals was a feature, not a bug, and wasn’t unique to Poland, it was widespread across Europe. Jedwabne. On July 10, 1941, 350 Jews were herded into a barn by their Polish neighbors and burned alive. In Radziłów, 800 more were murdered. In Szczuczyn, Jewish women were raped and killed in the streets. Pogroms swept Poland, many organized by Nazi decree, but many also by local initiative. In many cases the matches were lit by Poles.

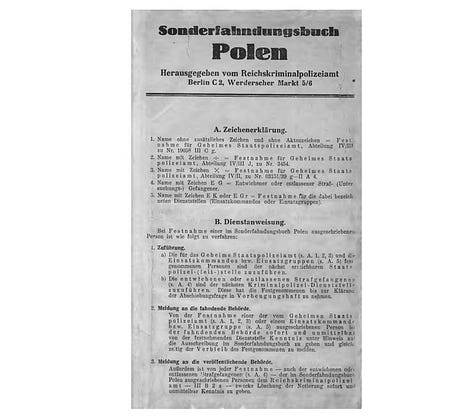

During the war, 200,000 Jews tried to survive in hiding—forests, attics, barns. The vast majority were caught. Not by the SS, but by szmalcownicy—Polish blackmailers, bounty-hunters, or ordinary villagers. In Warsaw alone, some 3,000–4,000 people acted as blackmailers and informants. Estimates suggest hundreds of thousands betrayed. Tens of thousands of active collaborators, and many more complicit by silence or inaction. Historians estimate 10–15% of the Polish population assisted in some way—through denunciation, robbery, violence, informing, or obstructing rescue. Even more benefited passively—moving into seized Jewish homes, taking over businesses, or inheriting property stripped from the murdered.

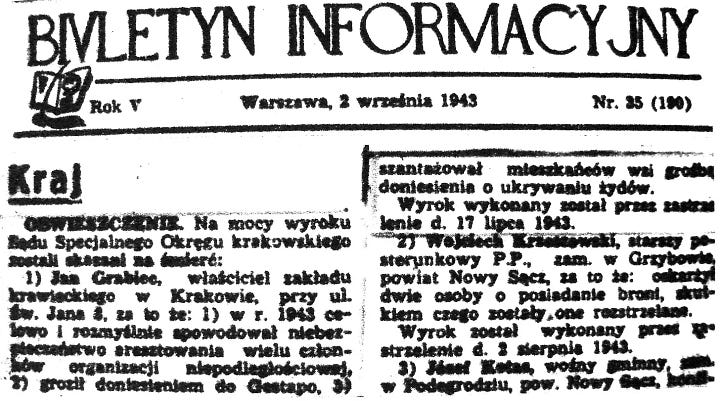

Of the 3.3 million Jews who lived in Poland before the war, 90%—about 3 million—were murdered. The highest number of any country in Europe. And yet, while Poles suffered and resisted, Polish collaboration and complicity ran deep. That does not mean every Pole was a perpetrator. In 1942, the Polish government-in-exile in London did what few others dared: it tried to sound the alarm. A courier named Jan Karski risked his life to infiltrate the Warsaw Ghetto and a transit camp near Bełżec. He saw the unthinkable and carried the evidence west. In December of that year, Polish foreign minister Edward Raczyński delivered a note to the Allied governments detailing the Nazi extermination campaign—The Raczyński Note—marking the first irrefutable diplomatic acknowledgment that the Holocaust was underway. The world knew. And it did almost nothing.

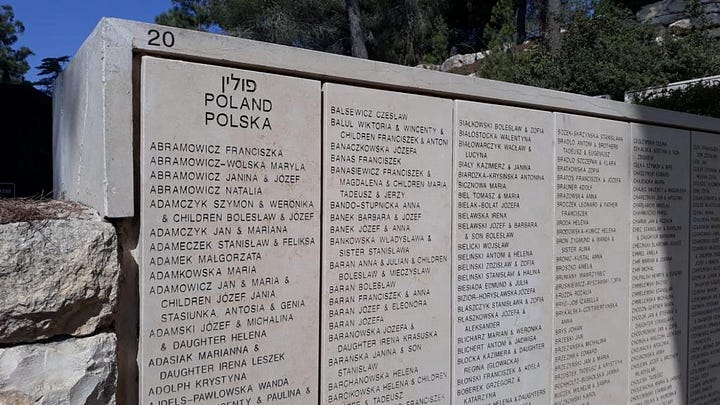

Today, over 7,200 Poles have been recognized by Yad Vashem as Righteous Among the Nations—the highest number of any country. Many were farmers, teachers, nuns, or priests who risked everything to hide a neighbor, smuggle food, or forge a document. They are heroes. But they were less than 1% of the population. For every Pole who helped, dozens looked away—or worse.

After liberation, Jewish survivors returned to find their homes looted, their families gone, and their neighbors hostile. Around 1,500 Jews were murdered after the war’s end, simply for returning. The 1946 Kielce pogrom, where 42 Jews were massacred in a single day, was the most notorious—but not the only one. In dozens of towns, survivors were attacked, driven out, or shot. Why? Because they were Jews, because they came back. This violence caused a massive exodus of more than 75,000 Holocaust survivors, who found their homes looted and neighbors hostile.

The betrayal didn’t end with blood. It became law. From 1945 onward, most Jews were denied restitution of property that had been stolen during the war. Their homes, shops, synagogues, and land—seized first by Nazis, then inherited by locals or the Communist state—remained out of reach. For decades, Poland passed no comprehensive restitution law. Survivors were told to forget. Their property was nationalized, or handed over to strangers. Many Jews fled the country a second times. From 1939 to 1989, virtually all Jewish-owned property was expropriated, nationalized, or transferred to others. Even after the fall of communism, Poland refused to legislate full restitution.

Poland might be a nation of victims. And to a large extent, it was. But victimhood is not moral immunity. History doesn’t ask how a nation wants to be remembered. It asks what actually happened.

And what happened to Polish Jews is this:

90 percent of Jews in Poland were exterminated, mostly by Germans.

But they were also betrayed by Poles.

They were shot in forests.

They were suffocated in barns.

They were handed over for cash, or out of spite.

Their homes were looted.

Their neighbors watched.

Their rescuers were few.

Their killers were not always strangers. Many were their neighbors who took their homes.

In 2021, a new law imposed a 30-year statute of limitations on Holocaust-era property claims—effectively extinguishing the last legal hopes for thousands of survivors and their families. Poland remains the only EU country without comprehensive Holocaust-era property restitution legislation. Israeli leaders condemned the bill as “immoral,” a “disgrace,” and “a shameful disregard for the memory of the Holocaust.” Poland’s leaders responded by summoning ambassadors and insisting the matter was closed, canceling Israeli visit.

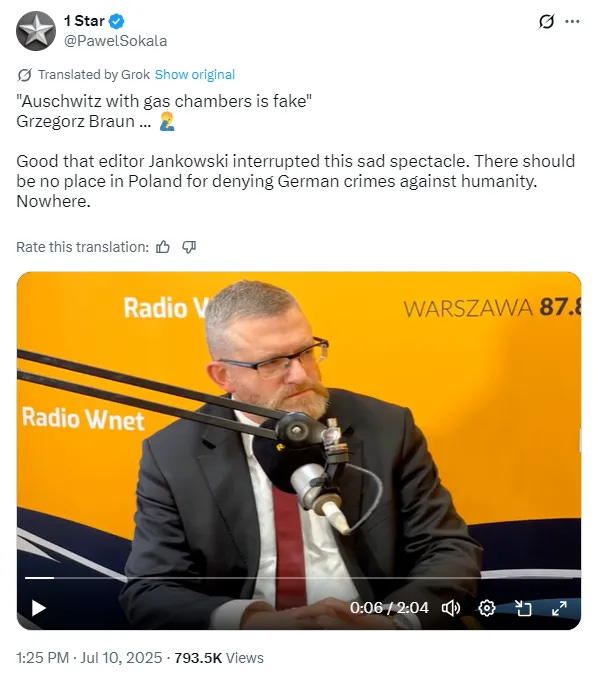

To question that narrative in Poland today is to invite outrage—or prosecution. The 2018 law criminalizing accusations of Polish complicity was not about historical truth. It was about national ego. Though the criminal penalty was softened under international pressure, the message remains: speak of Jedwabne, Kielce, or the szmalcownicy, and you may be prosecuted. Scholars have been sued. Museums have been censored. Truth itself has been put on trial. In a bitter irony, Holocaust denial is punishable by law in Poland—but so is acknowledging the uncomfortable truth that some Poles helped make it happen. Denial is forbidden, but so is honesty.

Poles suffered. They resisted. They died. That cannot be denied. But it does not absolve complicity. Pain does not equal innocence. To remember the Holocaust is to remember all of it—not just the parts that flatter some. To honor the dead is to name their killers honestly, even when the answer is uncomfortable. Because a nation that lies about its past is always one step away from repeating it.

Poland is not just wrestling with its past—it is repeating it. Antisemitism is once again bleeding from the margins into the mainstream, fueled not only by extremists but by politicians, pundits, and public institutions. Government officials have downplayed or outright denied Nazi crimes, while state media and education campaigns recast history to cast Poles solely as victims.

Jews face exclusion and hostility, echoing the “ghetto benches” of the 1930s and boycotts—this time under the banner of “anti-Zionism” or “patriotic values.” Far-right marches chant antisemitic slogans in city centers, tolerated or even defended by officials. Instead of confronting the crimes of the past, Poland is laying the groundwork to repeat them—this time with Palestinian and their own flags waving and history books rewritten.

Never forget is a promise.

Never again is now.

What makes this even more disgusting is that Poles are one of the few nations/people who risked their own lives at their own expense to hide and save Jews and this is the thanks they get: Descendants like you who spits on them and paint victims as perpetrators. Do not expect anyone to give you a hand if/when your people are persecuted again, you will obviously smear them. You need to reflect.

Jewish pathology is one of the most interesting phenomenons. Your people are actively committing a genocide against Palestinian Arabs right now, but sure let’s focus on some obscure irrelevant events from over 80 years ago. You’re an ungrateful bunch who spits on your own saviors.