The Right of Land Conquest in Defensive Wars: A Pre-1967 Perspective in International Law

A Historical Overview of Land Conquest

The question of whether land conquest in defensive wars is legitimate under international law has long been a contentious issue. Before 1967, international legal principles were evolving rapidly, moving away from the older norms of territorial conquest while still grappling with the nuances of defensive conflicts. This piece explores how international law treated the acquisition of territory in defensive wars before 1967 and how the framework began to shift toward the modern prohibition against conquest after the six-day war against Israel.

A Historical Overview of Land Conquest

1. Early Acceptance of Conquest

Before the 20th century, conquest was widely accepted as a legitimate means of acquiring territory. Under the principle of might makes right, wars often resulted in territorial annexations formalized through treaties. Examples abound in history: the Napoleonic Wars, colonial conquests, and shifting borders in Europe were all governed by this permissive norm.

2. The Post-World War I Shift

The devastation of World War I sparked a reevaluation of conquest. The establishment of the League of Nations in 1920 signaled the international community’s desire to curtail wars of aggression. The Covenant of the League promoted peaceful dispute resolution but it did not include prohibiting territorial acquisition through war, particularly defensive war.

The Kellogg-Briand Pact of 1928 further built upon this foundation, with signatories renouncing war as a tool of national policy. However, like the League Covenant, the pact primarily targeted aggression and left defensive wars outside the limitation.

The UN Charter and Defensive Wars

The signing of the United Nations Charter in 1945 marked a turning point in the international legal order. Two key provisions of the Charter influenced the discourse on territorial conquest:

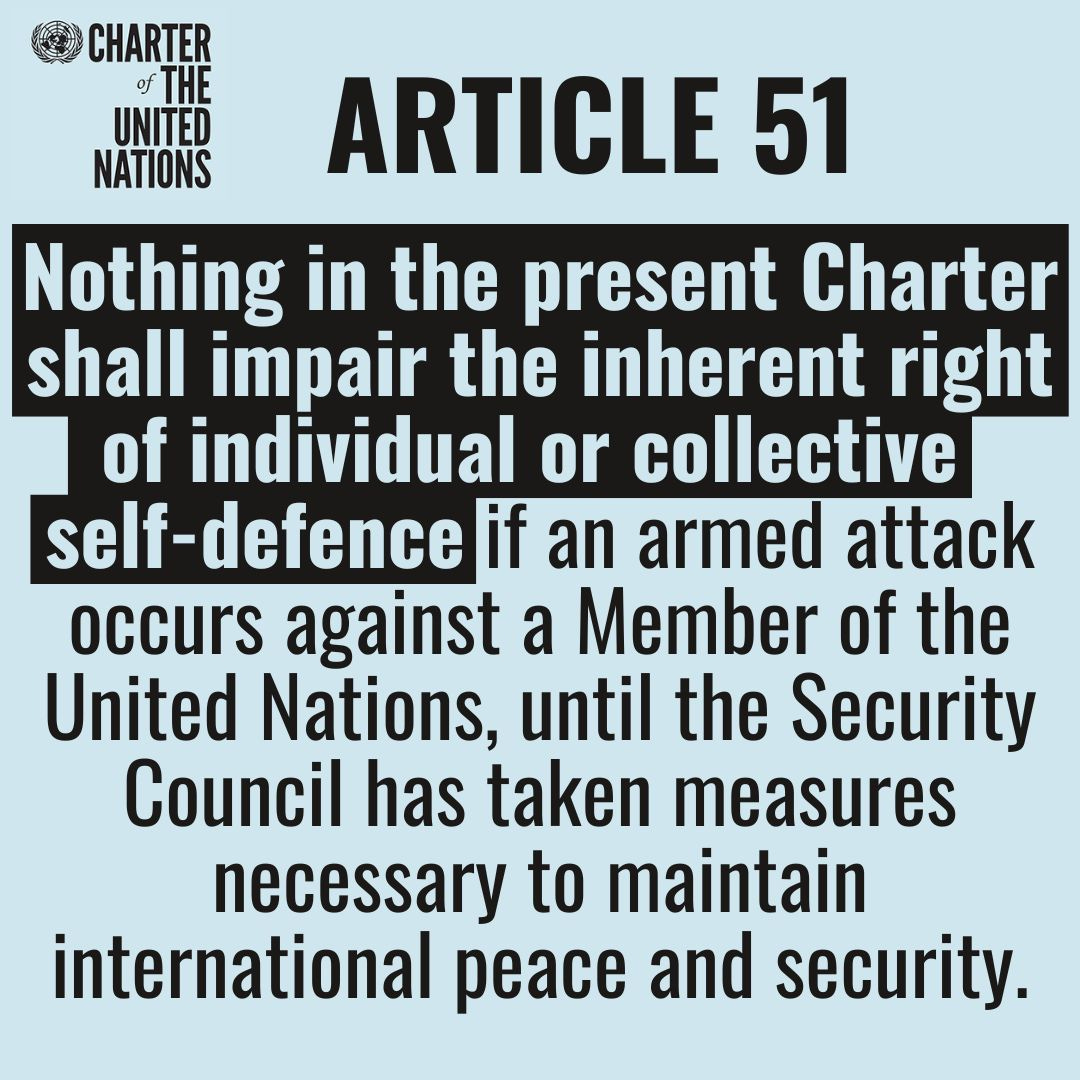

Article 2(4): Prohibited the use or threat of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state.

Article 51: Recognized the inherent right of self-defense if an armed attack occurred.

While these provisions emphasized the importance of territorial integrity, they did not explicitly prohibit land acquired in self-defense. This left land acquisition, especially when defensive wars were deemed necessary to ensure national security.

Customary International Law on Defensive Wars and Territory

1. Defensive Wars as a Justification

Customary international law historically treated defensive wars as an exception to the total prohibition on territorial conquest. A state acting in self-defense could retain captured territory essential to its future security. This view was used to legitimize territorial acquisitions following defensive conflicts.

2. Legal Precedents

Despite the growing focus on territorial integrity, legal precedents before 1967 demonstrated the legitimacy of territorial gain in defensive wars. For instance:

World War II Aftermath: The Allied Powers justified retaining or redistributing territory for security reasons, such as the division of Germany and the annexation of parts of Eastern Europe by the Soviet Union.

China and Tibet (1950–1951): China asserted control over Tibet after a military invasion in 1950, formalizing its claim through the Seventeen Point Agreement in 1951.

India and Hyderabad (1948): India annexed the princely state of Hyderabad through "Operation Polo," citing security concerns after the state's ruler sought independence.

India and Goa (1961): India’s annexation of Goa from Portugal was defended as a measure of self-defense, reflecting how states could have territorial acquisition in defensive terms.

Indonesia and West Papua (1962–1963): Following military pressure and a UN-brokered agreement, Indonesia took control of West Papua from the Netherlands under the 1962 New York Agreement.

Israel and Defensive Wars Before 1967

The 1948 Arab-Israeli War offers a notable example of how international law treated territorial gains resulting from defensive wars after the six-day war. Following its War of Independence, Israel retained territory beyond the boundaries outlined in the 1947 UN Partition Plan. While armistice agreements established ceasefire lines, they were not recognized as formal borders but indicated a degree of acceptance of territorial realities resulting from defensive actions. As the only emerging state after the end of the British Mandate and based on the principle of Uti possidetis juris the entire territory between the Jordan river and the Mediterranean sea is sovereign Israeli territory, according to customary international law

The Turning Point: The Six-Day War (1967)

The Six-Day War marked a watershed moment in the discourse on land conquest in defensive wars. Israel, acting in self-defense, captured Judea, Samaria, East Jerusalem, Gaza Strip, Sinai Peninsula, and Golan Heights. The international response—particularly UN Security Council Resolution 242. Resolution 242 emphasized the “inadmissibility of the acquisition of territory by war,” reflecting the shift toward an unequivocal rejection Israel’s right to defensive acquisition of territory.

The Double Standard

Before 1967, international law treated the conquest of land in defensive wars with notable ambiguity. While aggressive conquest was increasingly condemned, defensive wars often provided a legal allowed states to justify territorial acquisitions. The principles enshrined in the UN Charter, combined with post-World War II practices, began to shift the norm against aggressive conquest. The Six-Day War changed the stance that territorial acquisition, regardless of the circumstances, is inadmissible under international law.

After 1967, there are a few examples where the United Nations did not strongly condemn territorial acquisitions, even when they were framed as defensive actions. Some instances include:

The Falkland Islands (1982): When Argentina invaded the Falkland Islands (Malvinas) in 1982, the UK responded with military force. While the UN called for a peaceful resolution, the international community, including the UN, did not condemn the UK’s military response, as it was seen as an act of self-defense to reclaim the territory.

Turkey's Invasion of Cyprus (1974): After a Greek-led coup in Cyprus, Turkey invaded the northern part of the island, citing self-defense and the protection of Turkish Cypriots. While the UN condemned the invasion and called for a ceasefire, it did not demand that Turkey withdraw immediately. Over time, Turkey maintained control of Northern Cyprus, though it has not been widely recognized by the international community.

This evolution reflects a double standard in the commitment to territorial integrity, peaceful conflict resolution, and the rule of law. Understanding this historical trajectory reveals inconsistencies in sovereignty under international law.