Reviving an Indigenous Language: The Miraculous Revival of Hebrew

December 12, 1913, a Turning Point for Reclaiming Jewish Indigenous Identity

The Miraculous Revival of Hebrew is unique in history, showcasing how a language once considered "dead" could be revitalized to become a living medium for millions. The story of Hebrew is not just about one man's vision; it is a testament to collective effort, cultural resilience, and the power of language to unify communities across time and space.

111 years ago, On December 12, 1913, a pivotal moment in the revival of the Hebrew language occurred when it was officially adopted as the official language in Jewish schools in Ottoman Empire Syria-Palestina. This decision marked a significant step in a broader movement that sought to reestablish Hebrew not only as a liturgical language but also as a spoken and written language for everyday use among Jewish communities. It represented an essential element of the Jewish people's efforts to decolonize their homeland and reclaim their indigenous identity.

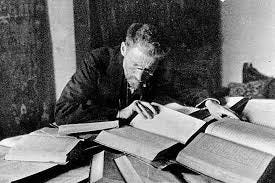

The revival of Hebrew began in the late 19th century, primarily driven by Eliezer Ben-Yehuda, who is credited as the "reviver" of the Hebrew language. He envisioned Hebrew as a unifying national language for Jews returning to their ancestral homeland, but he was not alone in this endeavor. His work was supported by a critical mass of individuals who believed in the revival of Hebrew as a national language for Jews returning to their homeland.

The development of Hebrew literature and media during the 19th century laid the groundwork for this revival. Newspapers like Ha-Magid and Ha-Melitz played pivotal roles in promoting Hebrew literacy and culture.. This movement gained momentum with the waves of Jewish immigration, known as the First and Second Aliyahs, which brought many young, idealistic immigrants eager to adopt Hebrew as their primary means of communication. These efforts were not merely about language; they were integral to the broader struggle for self-determination and cultural reclamation.

Challenges of Reviving a Dead Language

One of the primary challenges faced by those attempting to revive Hebrew was its historical association with religious texts. The vocabulary needed to adapt to modern life was largely absent. However, innovators began creating new words derived from biblical roots, allowing for the description of contemporary concepts. For instance, the modern Hebrew word for "machine," mechona, has its roots in biblical texts, showcasing how ancient language can adapt to modern needs.

Ben-Yehuda and other advocates recognized that education was crucial for the successful revival of Hebrew. They established schools where Hebrew was taught across all subjects, ensuring that children would grow up speaking it fluently. This approach was essential for creating a new generation of Hebrew speakers, thereby embedding the language into daily life and culture. In 1905, the first non-religious Hebrew-speaking school was established in Yafo, followed by others in Jerusalem.

These institutions played an essential role in ensuring that children grew up speaking Hebrew as their mother tongue. Ben Yehuda’s son, Itamar, became the first native Hebrew speaker since biblical times, symbolizing a significant milestone in the revival of the Jewish people’s indigenous language. By 1914, approximately 60 institutions were using Hebrew as their sole language of instruction, reflecting its growing acceptance and usage within the community.

Official Recognition under British Mandate

The British Mandate for Palestine, established after World War I, further solidified Hebrew's status. Article 22 of the Mandate declared English, Arabic, and Hebrew as the official languages of the British Mandate for Palestine. This recognition was unprecedented; it was the first time in over two millennia that Hebrew held official status in its historical homeland. The British authorities acknowledged the importance of Hebrew to the Jewish population and supported its use in administration and public life.

December 12, 1913, stands as a landmark date in the history of the Hebrew language revival. The official use of Hebrew in schools symbolized not only a linguistic transformation but also a broader cultural renaissance that would shape Jewish identity. This revival is unique in history, showcasing how a language once considered "dead" could be revitalized to become a living medium for millions. It underscored the Jewish people's connection to their homeland and their commitment to decolonizing not just their territory but also their cultural heritage through the revival of their ancestral language.