Public Service or Public Control? What the BBC Doesn’t Want You to Know

The BBC: Where Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four Was Born

Seventy-four years ago, on July 5, 1954, the BBC aired its first daily television news bulletin, News and Newsreel. It was stilted and awkward—narrated off-screen by Richard Baker over grainy footage and still photos. Presenters were forbidden from appearing on camera, for fear their faces might “distract audiences.” It would be another three years before Baker was seen on screen.

What was born that day was never a free press—it was government-scripted storytelling, upgraded with better production value.

The public was unimpressed. One viewer called it “absolutely ghastly.” Another said it resembled “the fat stock prices.” Though now romanticized as the birth of televised journalism, it was nothing of the sort. It was simply a new format for an old purpose: state-controlled messaging disguised as public service.

As we mark 74 years since that first bulletin, it’s not worth listing every way the BBC has failed to inform the public. One truth matters more: the BBC was never designed to deliver editorial freedom, impartial journalism, or truth. It was—and remains—a government-controlled institution.

To understand the BBC, we must turn to one of its most reluctant employees: George Orwell.

From 1941 to 1943, Orwell worked for the BBC Eastern Service, producing propaganda for India and Southeast Asia during WWII. He joined as a patriot but left disgusted by the censorship, script rewrites, and intellectual suffocation.

“Every script was screened. Every truth softened. Every contradiction erased,” he recalled. He later described the BBC as “half Jesuit, half whore.”

He left and wrote Nineteen Eighty-Four.

Broadcasting the Empire

The BBC’s crown control was evident long before television. In 1932, it launched the Empire Service, a shortwave broadcast network meant to “unify” the British colonies. Its inaugural broadcast? A Christmas Day message from King George V—ghostwritten by Rudyard Kipling—praising “imperial brotherhood.” It was government policy broadcast to the world.

Though the BBC experimented with television in the 1930s, it suspended all TV broadcasts during WWII. Orwell, then working at the Eastern Service, saw it firsthand. His job: craft messages to boost morale and counter Axis narratives. But behind the microphone, he found was complete government control:

In private, Orwell called the institution “half Jesuit, half whore”—a servant of moral superiority and government desires. When he later wrote 1984, the Ministry of Truth was modeled on his time at the BBC—not as fiction, but as memory.

“The atmosphere of the BBC is something halfway between a girls' school and a lunatic asylum… a mixture of Jesuitical discipline and sexual frustration.”

After WWII, the Empire Service became the Overseas Service in 1948, and then the World Service in 1965. The name changed. The mission didn’t. During the Cold War, it beamed NATO-friendly narratives into Africa, Asia, and Eastern Europe, projecting Britain’s voice—and values—across the post-colonial world.

A Structure Built for Control

From its creation in 1927 to 2007, the BBC was overseen by a Board of Governors—handpicked by the government. These weren’t watchdogs; they were gatekeepers, enforcing the state’s definition of “the national interest.” Though technically appointed by the monarch, they were chosen on the advice of the Prime Minister and Culture Secretary.

In 2007, the Board was replaced by the BBC Trust under public pressure—but it was mostly window dressing. Members were still appointed by politicians. Their job: promote, police, and protect the BBC—while enforcing the Royal Charter. That Charter isn’t symbolic—it legally binds the BBC to government objectives. Every ten years, its mission is rewritten. Its funding is reviewed. Its independence, redefined.

In 2017, the BBC Trust gave way to the BBC Board—hailed as modernization, but in reality, it centralized control further. The Chair is appointed by the monarch on the Prime Minister’s advice. Non-executive directors are nominated by ministers. The Director-General operates under a Framework Agreement dictated by the government.

In 2021, Richard Sharp—a former banker who helped Boris Johnson secure a private loan—was appointed BBC Chair. A reward, not a coincidence.

The names change. The structure doesn’t. And the structure guarantees obedience.

The Illusion of Independence

The BBC’s funding is not “publicly supported” in any meaningful sense of independence. Domestically, it’s funded by a license fee—a mandatory charge backed by criminal penalties, set by Parliament, and reviewed by the Treasury.

That leash is routinely yanked. In 2022, Culture Secretary Nadine Dorries froze the license fee and announced plans to abolish it by 2027—days after the BBC reported on Boris Johnson’s scandals. The message was clear: align or be defunded. The BBC’s reply? Message received.

While primarily funded by the UK license fee, also receives grant funding from the Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO) That’s not for “support”—it’s soft power abroad.

Even regulation is political. Until 2017, the BBC was regulated by government-appointed bodies—the Governors, then the Trust. Since 2017, Ofcom has overseen it—another government-appointed body, reporting to Parliament, not the public. Its role isn’t to defend independence; it’s to enforce ideological discipline: national security, social cohesion, and diplomatic alignment.

During crises, the government “guides” coverage. After the Iraq War began, Downing Street pressured the BBC to avoid criticism. After the Queen’s death, the BBC suspended all programming for 10 days. It became royal PR.

When the BBC reclassifies terrorists as hostages or censors the word “terrorism” from headlines, it isn’t speaking independently—it’s speaking for Whitehall. These decisions are reviewed, cleared, and implemented by editorial controllers operating within a structure dictated by the state.

A Digital Megaphone for the British State

What the Cold War was to radio, the internet is to today’s information war—and the BBC has evolved with it. Beyond radio and TV, it now operates a vast digital network of news syndication, social media channels, and mobile-friendly platforms. It supplies content to countless foreign outlets—some authoritarian, others nominally independent.

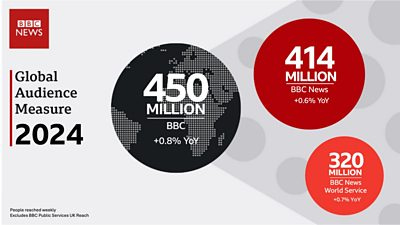

Today, the World Service reaches 456 million people in over 40 languages. It avoids calling Hamas a terrorist group. In Russian, it stays neutral on Ukraine. In Farsi, it dances around Western alliances. Every region gets a curated message—not crafted for truth, but for diplomacy.

It has always been strategic communications and foreign policy, camouflaged as reporting, seen as “the most trusted and reliable international news provider.”

Its global-facing newsroom produces region-specific content, always within editorial guidelines shaped by UK foreign policy. Headlines are softened. Sources are filtered. Controversial facts—such as those implicating UN agencies, Palestinian terrorists, or British allies—are framed to fit political goals.

It looks like journalism. It functions as messaging.

A Web of Strategic Partnerships

Since 2011, the BBC has partnered with Al Jazeera English—Qatar’s state-run broadcaster. Documentaries are rebroadcast. Some are co-produced. This isn’t just syndication—it’s ideological alignment.

Al Jazeera launched in 1996, just after the BBC shut down its Arabic service. Many of its founding staff were ex-BBC, including Ahmed Al Sheikh. Ahmed Al Sheikh was instrumental in the rise of Al Jazeera as the powerful media house it is today. Al Jazeera presented itself as an independent “Arab voice,” but from the beginning it was known that it is meant to serve Qatari state interests.

Qatar funds the Muslim Brotherhood. The UK trades with Qatar. The BBC partners with Qatar. See the pattern?

In some languages, the BBC avoids criticizing Qatar. In others, it mirrors Al Jazeera’s tone—especially on Israel, Iran, or Islamist movements. This is not an accident. Always remember, it’s government messaging—soft power in “journalistic” form.

The BBC’s Royal Charter requires it to reflect “religious diversity,” which it fulfills in part by consulting a Muslim Consultative Group—the only faith with a formal advisory panel. No similar body exists for Jews, Christians, or any other faith. These consultations shape language and editorial tone. So when the BBC decides to broadcast Eid prayers, avoids calling Hamas terrorists or refers to Palestinian militants in prison as “hostages,” it isn’t independent journalism—it’s state-aligned messaging, structured into the Charter itself. A 2015 UK government report warned of Muslim Brotherhood influence in British institutions, including media. Coincidence?

The Lie Became the Truth

In 1984, Orwell described a world ruled by a Ministry of Truth that rewrites history, erases facts, and manufactures consensus. Its motto:

“Who controls the past controls the future. Who controls the present controls the past.”

Sound familiar?

Propaganda today isn’t crude. It’s slick, calm, and well-lit. The BBC no longer bans dissent—it marginalizes it. Labels it “fringe.” Silences it by omission.

You won’t hear critiques of multicultural failure, radicalization in British cities, or Israel’s side of the story without a heavy filter. You won’t hear how UN agencies enable terror. Why? Because the system funding the BBC is the system it was built to protect.

Orwell’s 1984 wasn’t just fiction—it was a warning shaped by experience.

The BBC rewrites the past. It reframes the present. It engineers perception through language.

In 1984, the slogans were chilling:

“War is Peace.”

“Freedom is Slavery.”

“Ignorance is Strength.”

At the BBC, the slogans are softer:

“Trusted Worldwide.”

“Independent.”

“Public Service Broadcasting.”

But the function is the same: to manufacture consensus, frame narratives, and ensure that government policy looks like moral truth—while opposition is labeled misinformation.

The BBC is unique among broadcasters: mostly paid by the taxpayers, funded in part by the Foreign Office, governed by ministerial appointees, and bound by a Royal Charter to serve state objectives. The BBC is not a media outlet. It is a state controlled organization with global reach. It is designed to serve the interests of every UK government — Labour, Conservative, or coalition — for nearly a century.

It is not independent.

It is not neutral.

And it is not truth.

As Orwell wrote:

“The past was erased, the erasure was forgotten, the lie became the truth.”