Margot Was the First Target. Anne Was the Last Voice.

July 6, 1942, the Frank family Went into Hiding

Today, 83 years ago, On July 6, 1942, the Frank family disappeared. Not into thin air. Into fear. Into silence. Into an annex that wasn’t ready, because the world they had once believed in had already collapsed.

They left their home in Amsterdam with backpacks, bundled clothing, and trembling hands. They left food on the table and dishes in the sink—to make it look like they’d fled suddenly. The truth is, they had no more time to wait. A day before, July 5, Margot Frank had received a summons from the Nazis to report to a German "labor camp." Everyone knew what that meant.

So they ran—not because they had a solid plan, but because they had waited too long to make one.

Anne Frank became the voice the world remembers. Her diary—the story of a teenager whose optimism defied the horror closing in around her—became the universal symbol of lost innocence. She is quoted in schools and sculpted in bronze. Her face is known. Her words are taught. Her diary read by millions.

But Anne didn’t want to be a symbol. She was a child.

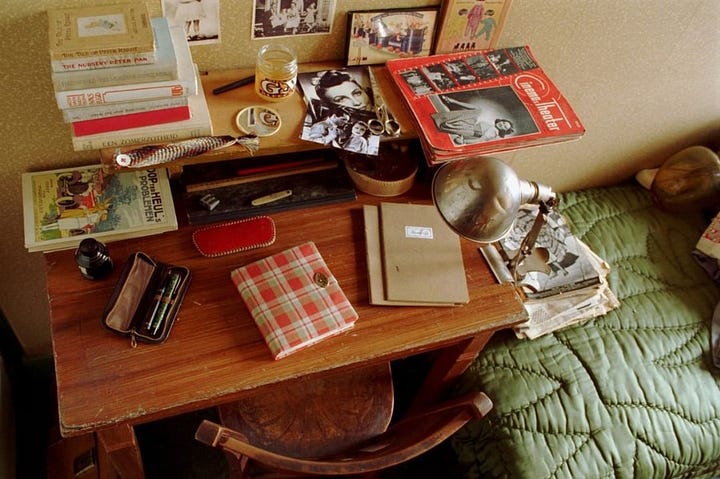

Anne Frank began writing long before she received her famous diary for her 13th birthday on June 12, 1942—just weeks before going into hiding. By the age of six, she was already crafting stories, jokes, and absurd tales about talking cats and mischievous princesses. Her writing often included cheeky humor that occasionally got her into trouble. She was loud, curious, moody, and brilliant—a vivid spirit even before the war forced her into silence.

She admired America, and she begged her father to take the family there. Otto Frank tried. He reached out to contacts, filed papers, even applied to Cuba. But the U.S. closed its doors—to the Franks, and to tens of thousands of other desperate Jewish families. Caught between Nazi terror and Western indifference, they were left with nowhere to go.

Anne also dreamed of Palestine. Not as an activist or a Zionist per se—but as a place where Jews could live freely. In the annex, she imagined life in Haifa. She saw herself walking safely in the sunlight.

Otto Frank considered this too. But emigration to British-controlled Palestine was nearly impossible. Britain’s 1939 White Paper had severely restricted Jewish immigration to appease Arab opposition. The quotas were low, the permits were scarce, and the bureaucracy was deliberately slow. Even Jews fleeing certain death in Europe found the gates of the Jewish homeland locked. The Franks simply could not get in.

But here’s the truth: the world already knew. As early as 1942, the Polish government-in-exile sent detailed reports to the Allies about the systematic extermination of Jews in Nazi-occupied Europe. One of the most damning was the Raczyński Note, delivered to foreign ministers across Allied capitals. It described, with horrifying precision, what was happening in the ghettos and camps. The West had been warned. They looked away and closed the doors.

As the Nazi grip on the Netherlands tightened, Anne changed her writing. She had heard a broadcast from the Dutch government-in-exile urging citizens to preserve letters and diaries as future evidence. That changed her approach. She began rewriting her diary, transforming it into testimony—not just memory.

She wanted to be a journalist or a novelist—someone who told the truth of what was going on. And though she still clung to hope, Anne began to understand the truth: they might not survive. She even wrote, with chilling clarity, that she wanted her words to live on even if she didn’t. She wasn’t writing to feel better. She was writing so the world could never say, “We didn’t know.”

That’s the Anne we remember.

But today, we must also remember Margot—because we almost never do. She appears in textbooks only as Anne’s sister. She is mentioned, not explored. Quoted rarely, remembered faintly. She left a diary, but we never read it because it was destroyed. She is the silence next to Anne’s voice. But Margot Frank lived, and dreamed, and feared, and wrote. And her story also deserves to be told.

Margot Betti Frank was born in 1926 in Frankfurt, Germany. Her early childhood was shaped by the Weimar Republic—Germany’s brief experiment in liberal democracy—and by her family’s identity as secular, assimilated German Jews.

The Franks were not Orthodox. They celebrated Jewish holidays, but they were part of the educated, middle-class Jewish world that saw itself as proudly German. Otto Frank had served as a lieutenant in the German Army in World War I. Edith Frank came from a devout family, but like many Jewish women of her generation, embraced a modern, cosmopolitan life. Their daughters were raised with books, music, and values.

In 1933, after Hitler seized power, the Franks left Germany for the Netherlands—joining thousands of German Jewish refugees who thought Amsterdam would be safe. And for a while, it was. Anne and Margot went to progressive schools. They learned Dutch. They made friends. But they also experienced exclusion. Even before full Nazi occupation, Anne and Margot—still marked by their German accent and their Jewish identity—were bullied and isolated. They were never fully at home

.

Margot Frank thrived academically. She was top of her class. Calm, elegant, thoughtful. Teachers adored her. While Anne was theatrical, Margot was reserved. She preferred poetry to parties, and logic to argument. She was seen by many as the ideal daughter—moral, intelligent, modest.

But Margot was far more than the perfect girl next door.

She was a keen observer of the world even before they went into hiding—deeply interested in history, law, and current events. At school, she took detailed notes on international affairs, trying to make sense of a world unraveling through systems and treaties. She was fluent in Dutch, German, and English, and had already begun learning Hebrew—not just as a religious act, but as a sign of belonging.

In the annex, she often listened to BBC broadcasts on the hidden radio, tracking the war’s progress through crackling static. Her thirst for knowledge and her quiet determination to understand the chaos outside made her both a student and a witness of history, not a silent one.

Before going into hiding, Margot had been active in a Jewish youth group that encouraged aliyah (emigration to Palestine). Quietly, without speeches or fanfare, she was preparing herself for a new life. She dreamed of becoming a midwife in the Jewish homeland—a dream rooted in healing, in rebuilding, in choosing life.

In the annex, she studied philosophy and law, kept to a daily routine, and wrote letters and also kept a diary of her own, none of which survived. Lost. No trace of it has ever been found.

Margot was also growing more spiritually connected. While the family was not religious in a traditional sense, Margot taught herself Hebrew and began teaching it to Anne. She fasted on Yom Kippur, even when no one else in the annex did. She connected with Judaism not just as identity, but as inner strength. Like many Jews in hiding, stripped of everything, faith became her final form of resistance.

She never argued. She never complained. When tensions rose in the cramped annex, it was often Margot who kept the peace. Anne, full of fire, sometimes resented that quiet perfection. But in moments of despair, she looked to Margot’s calm and resolve.

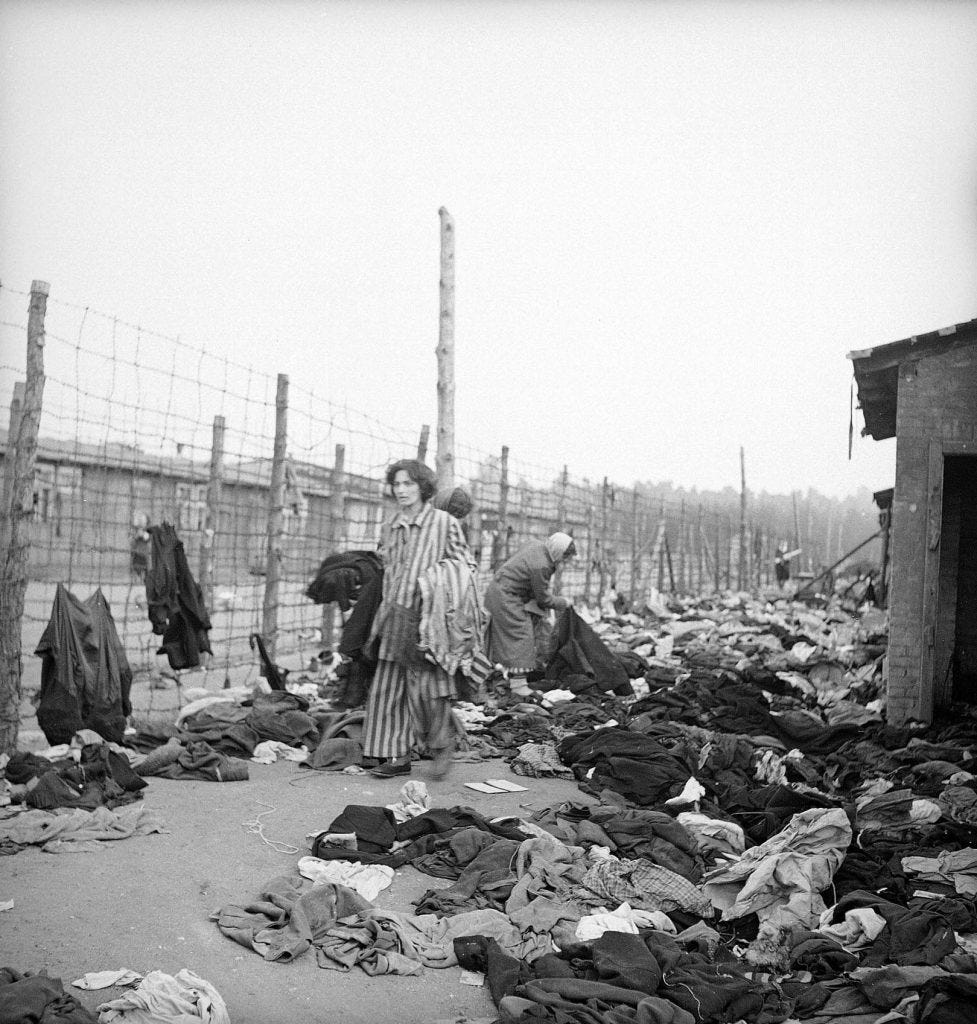

And yet, her story was swallowed. Margot's diary was never recovered. The paper trail ended when the family was betrayed—likely by a Dutch informant—and arrested by the SS in August 1944. They were sent first to Westerbork, then to Auschwitz. In October, Anne and Margot were moved again—this time to Bergen-Belsen, a chaotic, disease-ridden death camp near Berlin.

There, amid freezing cold, lice, and starvation, Margot collapsed from her bunk—too weak to stand. She died shortly after. Anne died a few days later, in March 1945, her spirit already broken by grief, illness, and the loss of her sister.

They died just weeks—possibly days—before British forces liberated Bergen-Belsen. Their mother Edith had died weeks before in Auschwitz. Otto survived. When he returned to Amsterdam, he found only one daughter’s voice had endured: Anne’s.

Anne’s best friend, Hannah Goslar, survived the camps. She lost Anne twice—first when the Franks went into hiding, and again when Anne died just weeks before liberation. By chance, the two briefly reunited through a fence at Bergen-Belsen. Anne was weak, freezing, and starving. Hannah passed food through the barbed wire, but it was too late.

Hannah survived. Her sister did too. Most of her family didn’t. After the war, she rebuilt from nothing—emigrated to British Mandate Palestine in 1947, became a nurse, married, and raised three children, 11 grandchildren, and over 30 great-grandchildren. Her life was the ultimate fuck you to the Nazis. They wanted to erase the Jewish people. She lived, thrived, and filled the world with more Jewish life.

She died in Jerusalem at 93—carrying Anne’s memory to the end.

And so Margot became a footnote. The quiet sister. The forgotten diary.

But she was not empty.

Margot was wise. Faithful. Determined.

She was observant, disciplined, and kind.

She was the reason the family went into hiding at all.

She was the first target.

She was the first of the sisters to die.

We remember Anne because she left words behind .

Today, hatred returns—in chants, on campuses, burned synagogues, in silence.

Jews are harassed, isolated, persecuted—again.

The rhetoric is modern. The hatred and violence is ancient.

And many still tell themselves it’s not that bad.

That it will pass.

But that’s what the Franks believed too.

They were educated, assimilated, respected.

They waited. They hoped. They trusted that things would stop.

They had no plan.

This time, no one can say they didn’t see it coming.

And to truly honor their memory, it’s not enough to remember or fight back—

this time, we must have a plan.

This time, we have Israel. We have our homeland back.

Every Jew needs a valid passport.