BDS Isn’t 20 Years Old — It’s a Centuries-Old War on Jews, Rebranded for the West

Long before hashtags, long before Israel existed, long before the first kibbutz was founded or a single so-called “settler” crossed a green line, boycotts already targeted Jews.

Every July 9th, social media fills with tributes to the so-called “Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions” movement—framed as a peaceful campaign for Palestinian human rights that began in 2005. For many, that’s the entire story: a hashtag, a list of brands to boycott, a protest chant outside Starbucks—all in the name of “human rights.”

But the movement is far older. Much older.

BDS didn’t begin in 2005—or in this century. It’s not a reaction to the Six-Day War, settlements, or borders. It’s the latest phase in a century-old campaign to isolate, punish, and expel Jews—especially those returning to their ancestral homeland.

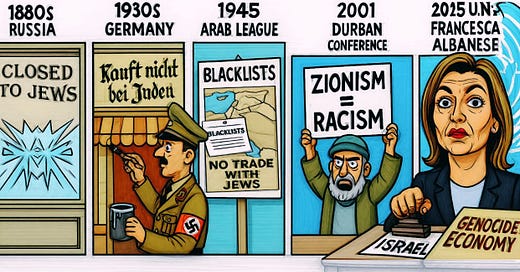

Long before hashtags or the first kibbutz, Jews faced organized boycotts designed to exclude them socially, economically, and politically. In the 1880s Russian Empire, pogroms combined violence with economic exclusion: Jewish shops were looted, then systematically shunned. Jews were barred from guilds and trade associations under legal restrictions.

In Nazi Germany in 1933, the first act was an economic boycott: Kauft nicht bei Juden—“Don’t buy from Jews.” Hungary followed in 1938, banning Jews from professions. Across Europe, nationalist movements pushed slogans like “Buy Christian only,” especially in Poland, where boycotts were endorsed by political parties and even state authorities.

These weren’t acts of conscience. They were declarations: You do not belong here.

Boycotts were hardly foreign to the Middle East.

In British Mandate Palestine, this strategy took early, brutal root.

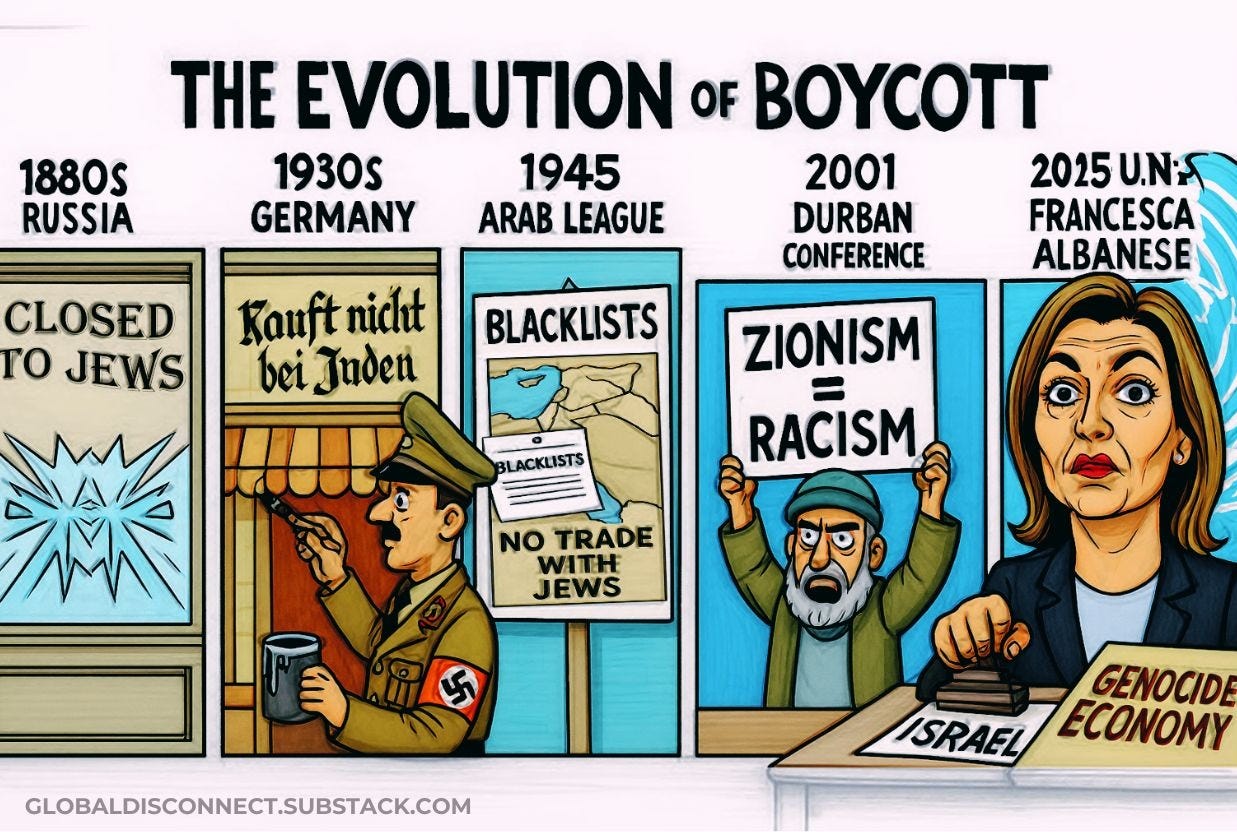

Haj Amin al-Husseini, the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, orchestrated organized boycotts against Jewish businesses—and incited violence against Arabs who defied him by trading or coexisting with Jews.

His chilling words were unambiguous:

"We will win through an economic boycott. The boycott in Moslem countries against Jewish industries is tight and daily growing tighter, until the industries will be broken and English friends, moved by pity, will remove the last remaining Jews on their battleships." Grand Mufti Haj Amin al-Husseini September 24, 1929

This wasn’t about borders—there were none.

It wasn’t about occupation—the land was under British rule.

It was about preventing Jewish life from being reestablished in Israel by any means.

This wasn’t rhetoric. It was a death sentence in the making.

In 1929, that incitement exploded into massacres. In Hebron and Safed, 133 Jews were slaughtered—stabbed, hacked, lynched by mobs, many neighbors. Yeshiva students were dragged from dorms and murdered. Children killed in their beds.

But Jews weren’t the only victims.

Many Arabs were murdered—not by Jews—but by neighbors for trading or coexisting with Jews.

This strategy expanded.

In 1945, before Israel’s independence, the Arab League imposed a sweeping boycott—not against Israel (which didn’t yet exist)—but against Jews in Palestine.

Long before war or refugees, Arab leaders sought to starve Jewish presence into submission.

The boycott was total: companies trading with Jews, companies trading with those companies, and international firms refusing compliance were all targeted. Blacklists. Economic coercion. Global pressure. And of course, at the time, Palestine was synonym for Jew.

The campaign didn’t stop with Israel’s founding in 1948. It escalated.

In the ’50s, ’60s, and ’70s, Arab states wielded oil wealth to pressure global businesses to sever ties with Israel. Blacklists grew. American, European, Asian companies were targeted.

This campaign struck not just Israel but American business and sovereignty.

Foreign governments told U.S. companies who they could and couldn’t trade with—demanding compliance with blacklists and questionnaires.

That crossed a line.

In response, Congress passed anti-boycott laws under the Export Administration Act of 1979—national security measures to protect U.S. sovereignty and commerce.

It became illegal for U.S. firms to:

Comply with foreign demands to boycott U.S. allies

Provide information for foreign blacklists

Answer questionnaires about business with targeted countries.

This commitment didn’t fade. In 2018, the Trump administration reaffirmed and tightened these rules to confront modern economic coercion.

Think about that.

The U.S. didn’t just condemn the Arab League boycott. It codified resistance into federal law—because allowing foreign regimes to dictate American commerce is surrendering independence.

This was never just about Israel.

It was about protecting American interests and ensuring U.S. foreign policy is made in Washington—not Riyadh, Cairo, or Tehran.

After many decades the Arab boycotts failed, largely due to the anti-boycott laws in the U.S.

Fast forward to July 30th, 2001. 13 Arab nations seeked to revive the boycotts. In order to get around the anti-boycott legislations they proposed to do it through a “non-governmental” boycott. Everything started in Tehran during a UN sponsored conference in preparation for the Durban 2001, it charged Israel of racism, apartheid, genocide and crimes against humanity. Jewish delegates were banned from the conference.

Durban became a platform for Holocaust inversion and historical distortion. Israel was branded apartheid, accused of genocide and crimes against humanity—charges echoed in official UN proceedings. At the NGO Forum, the mask dropped. Attendees handed out The Protocols of the Elders of Zion. Signs praised Hitler. Booths equated Zionism with racism. Calls for Israel’s destruction echoed.

The Arab League boycott was reborn as a movement for “justice.”

Words like “apartheid,” “colonialism,” and “right of return” became weapons—to delegitimize Jewish self-determination and advocate demographic replacement.

Durban didn’t create BDS. It refined it with a Western-friendly accent.

Two years later, in 2005, NGOs in Ramallah issued the “BDS call.”

Often treated as grassroots, even Norman Finkelstein admitted this “civil society” was mostly one-person operations—manufactured legitimacy and repackaged old messages.

Omar Barghouti, co-founder of BDS, laid bare its goal:

“Definitely, most definitely, we oppose a Jewish state in any part of Palestine.”

Not a West Bank state. Not two states. Not peace with conditions.

Any state. Anywhere. Ever.

This was never about borders. It was about existence.

If you think this movement is fringe, think again.

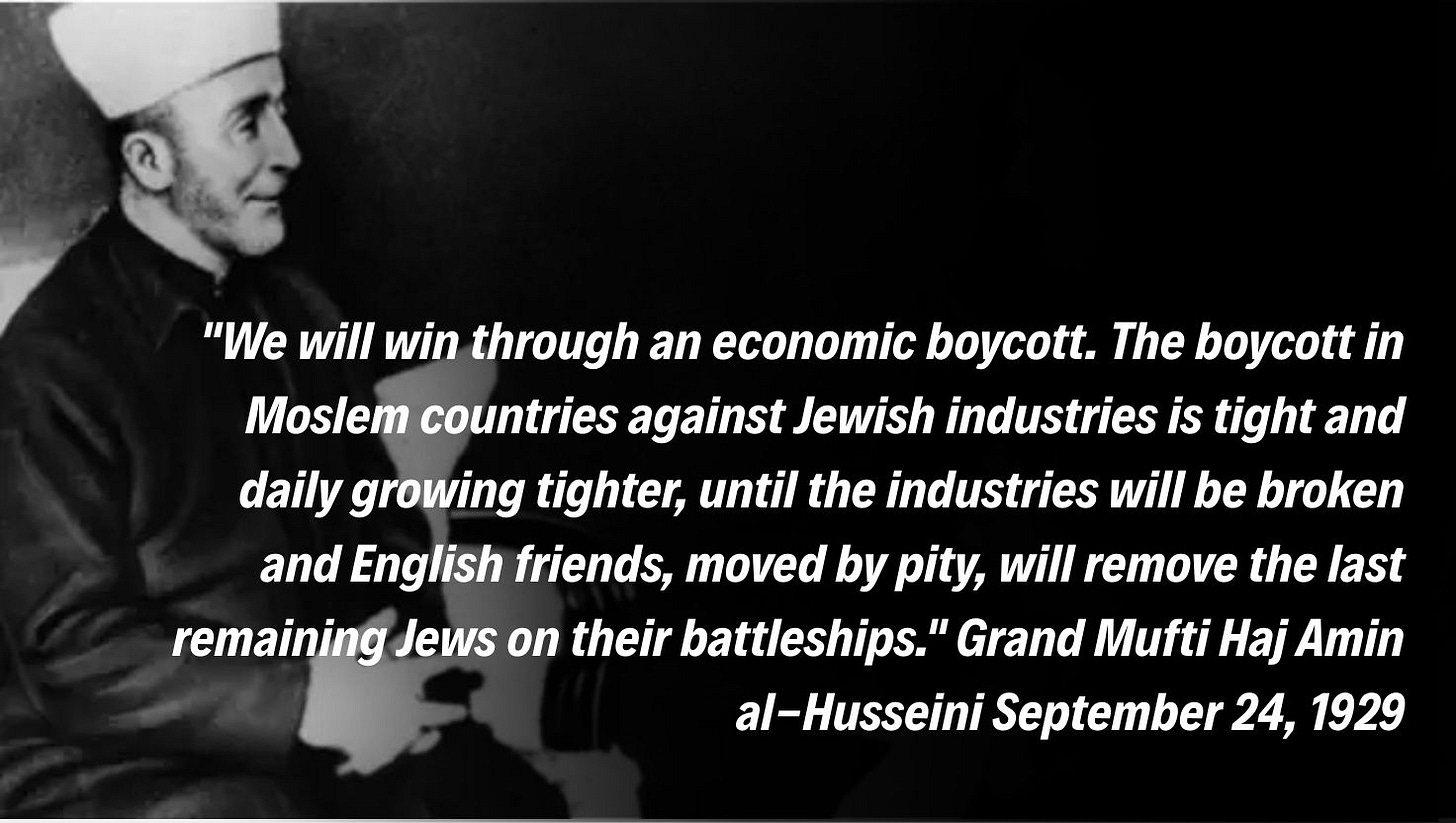

Last week, the UN Special Rapporteur on Palestinian territories, Francesca Albanese, branded Israel’s entire economy a “driver” of genocide in Gaza.

Not just the military. Not just the weapons.

The economy.

She demanded companies sever business ties with Israel, called for global economic disengagement and an arms embargo.

In effect, she called for Israel’s dismantling—not by war but by bankruptcy and isolation.

This is not diplomacy. It’s economic warfare with a UN letterhead.

From 1880s pogroms to 1930s Germany, from the Mufti’s riots to the Arab League boycott, from Tehran to Durban to Ramallah to Geneva—this is the same campaign.

It has changed slogans and branding but never its target.

When people chant “From the river to the sea,” demand unconditional “right of return,” or call to “dismantle Israeli apartheid,” they aren’t calling for peace.

They are calling for the end of Jewish sovereignty. For genocide.

That is not human rights work.

It is the oldest hatred in the world—dressed in a press release and a protest sign.

BDS is not a freedom movement.

It is a continuation movement.

It continues the boycotts of Russia, Germany, and Hungary. It echoes the riots of the 1920s and the Arab League’s resolutions of the 1940s.

It picks up where the Mufti left off—and where the UN now, shamefully, carries the torch.

Today I am imposing sanctions on UN Human Rights Council Special Rapporteur Francesca Albanese for her illegitimate and shameful efforts to prompt @IntlCrimCourt action against U.S. and Israeli officials, companies, and executives.

Albanese’s campaign of political and economic warfare against the United States and Israel will no longer be tolerated. We will always stand by our partners in their right to self-defense.

The United States will continue to take whatever actions we deem necessary to respond to lawfare and protect our sovereignty and that of our allies.

To recognize this is see history clearly.

The BDS movement didn’t emerge from nowhere.

It emerged from a legacy of exclusion, cloaked in new language, tailored for Western ears.

It didn’t start on July 9th, 2005.

It just got better at marketing.