4th of July: Freedom Isn’t Just Fireworks — Sometimes Comes in Flasks

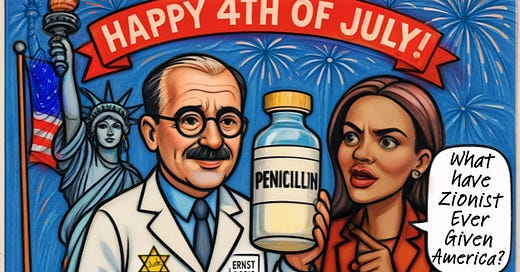

What Have Zionists Ever Done For America? Just Save 200 Million Lives Worldwide

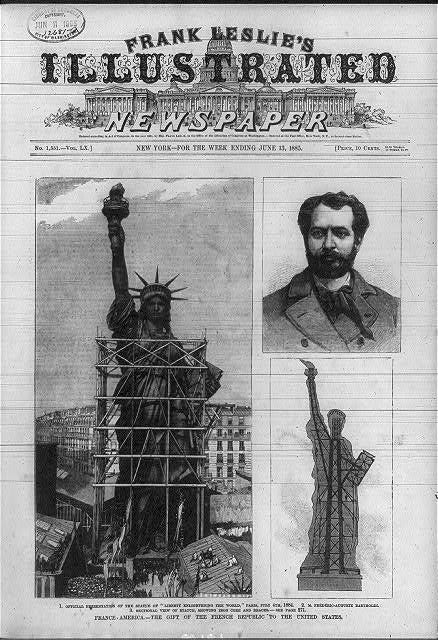

Every July 4th, Americans celebrate the birth of our nation — the adoption of the Declaration of Independence in 1776, a bold assertion of freedom, human rights, and self-determination. Nearly a century later, in July 4th, 1884, the Statue of Liberty was presented in Paris as a gift from France to America, it was presented to Ambassador Morton at a ceremony in Paris — a timeless symbol of liberty, hope, and the promise of new life for immigrants arriving on American shores.

These moments represent the spirit of freedom that defines the United States. But beyond the fireworks, speeches, and parades, July 4th also invites reflection on quieter revolutions — those born in laboratories, carried out by exiles, and dedicated to saving human life. One of the most extraordinary of these is the story of penicillin — the world’s first true antibiotic.

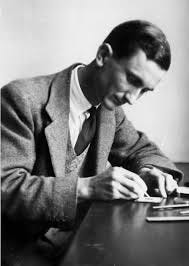

The story begins in 1928, when Scottish bacteriologist Alexander Fleming noticed that a strange mold — Penicillium notatum — prevented bacteria from growing in his petri dishes. It was a breakthrough, but one that remained inert. Fleming could not purify or stabilize the substance, and for over a decade, penicillin was a scientific curiosity, not a usable drug.

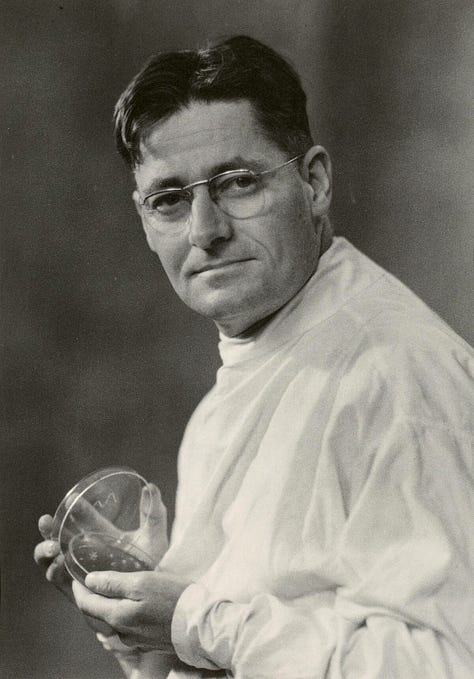

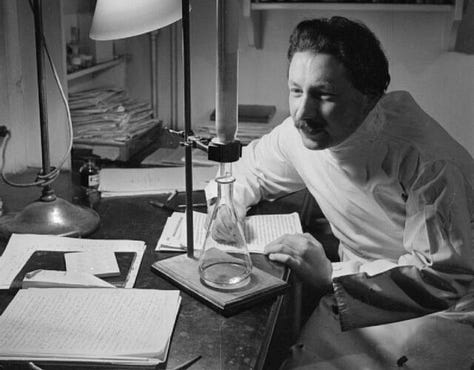

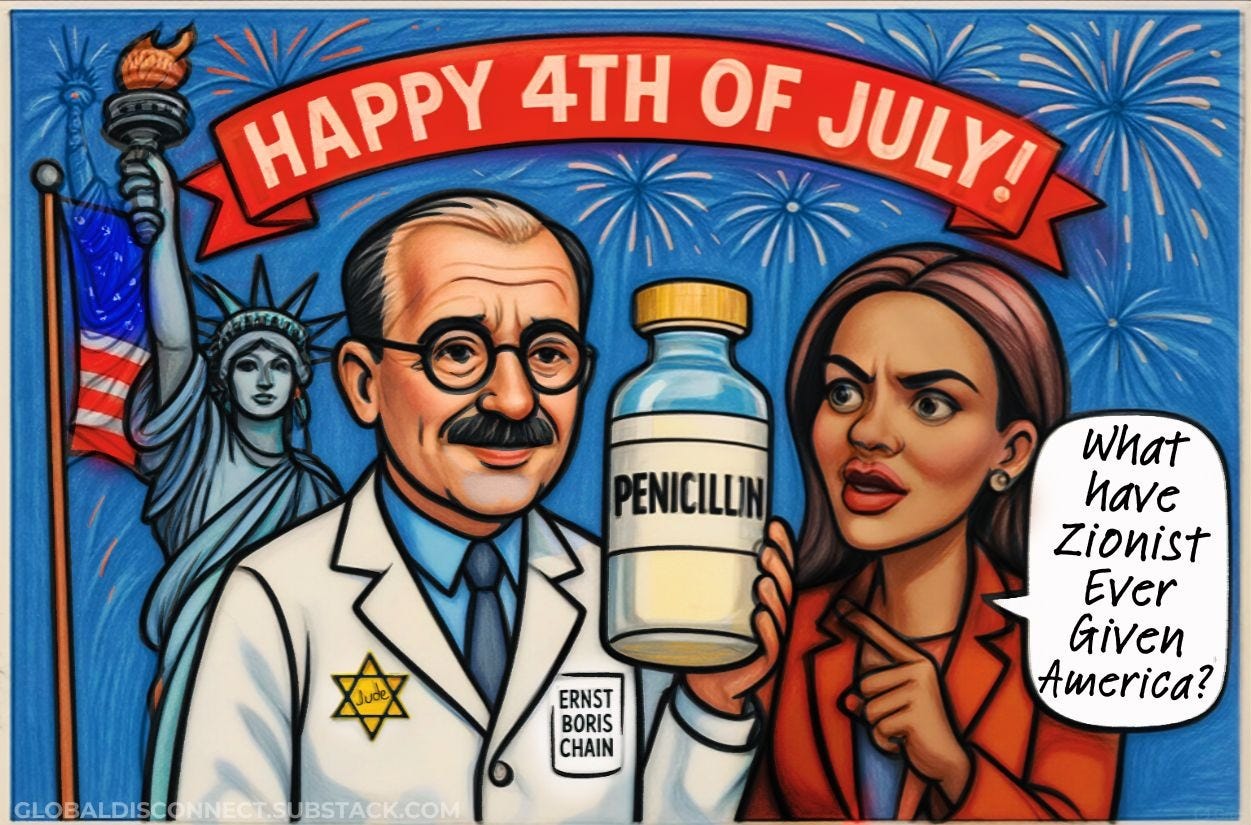

That changed in 1938, when a team at Oxford University — led by Australian pathologist Howard Florey — revisited Fleming’s findings. Florey, who had long been interested in the ways bacteria and mold naturally kill each other, came across Fleming’s paper on the penicillium mold while leafing through back issues of The British Journal of Experimental Pathology. Florey assembled a small group of collaborators, including British biochemist Norman Heatley and one of Florey’s brightest employees, Ernst Boris Chain, a Jewish refugee who had fled Nazi Germany in 1933.

Chain’s role was decisive. His expertise in biochemistry allowed him to isolate, purify, and stabilize penicillin — a feat no one else had achieved. Without Chain’s contribution, penicillin likely would have remained a footnote in scientific literature. Heatley’s innovations in extraction and production methods complemented Chain’s breakthroughs. Together with Florey, they turned an abandoned idea into a miracle drug.

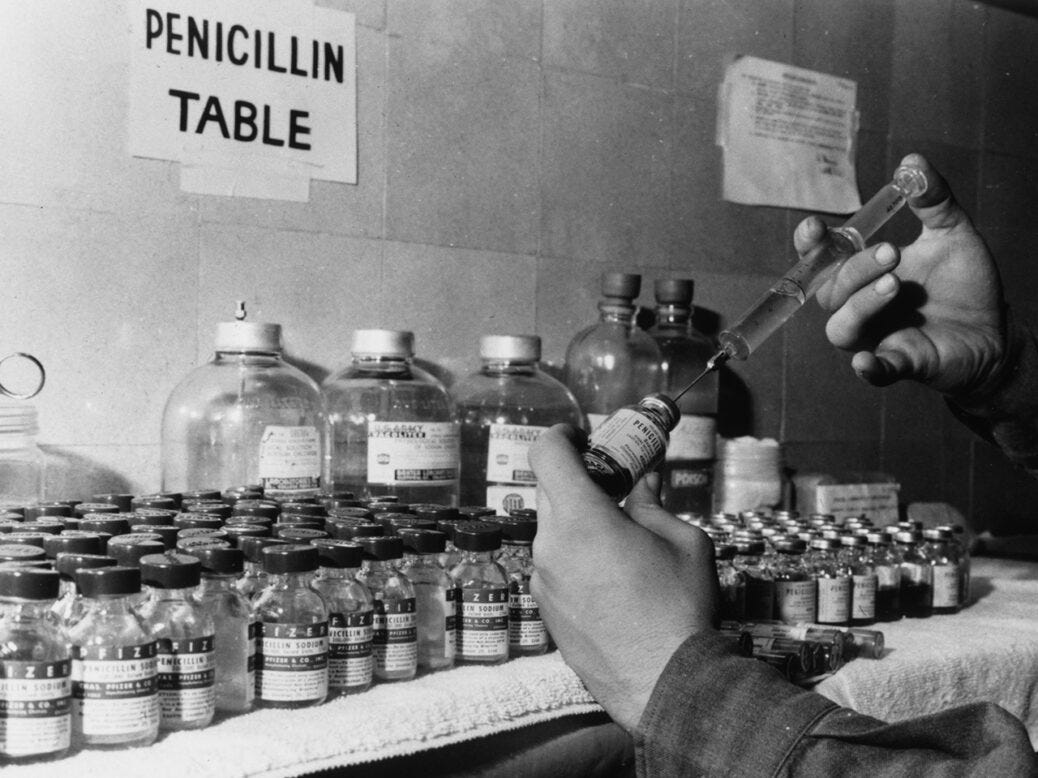

By 1940, animal trials had begun and the Oxford team successfully treated infected mice. By early 1941, they had conducted promising human trials. But they quickly ran into a major problem: they couldn’t produce enough penicillin to keep patients alive. The process was too slow, and the yield too small. Meanwhile, the war was escalating.

The team knew they needed help. So in a hot summer of 1941, Florey and Heatley traveled to the United States — timing their arrival to coincide with the July 4th weekend. The symbolism was intentional: they sought American partnership not just for logistical reasons, but in the spirit of shared values — freedom, hope, and international cooperation to save lives.

They attended a Fourth of July gathering hosted by John Fulton, a prominent physiologist and friend of Florey. The event brought together key scientists and allies who helped introduce them to American pharmaceutical companies and government officials.

The gamble worked. By late 1941, American manufacturers began working around the clock to develop scalable penicillin production. And what began at a Fourth of July weekend party, spark interest in penicillin, planting the seeds of collaboration. That informal encounter led to a transatlantic partnership that turned penicillin into a mass-produced miracle—one that would change the fate of allied soldiers in WWII, the course of modern medicine and has saved millions of lives.

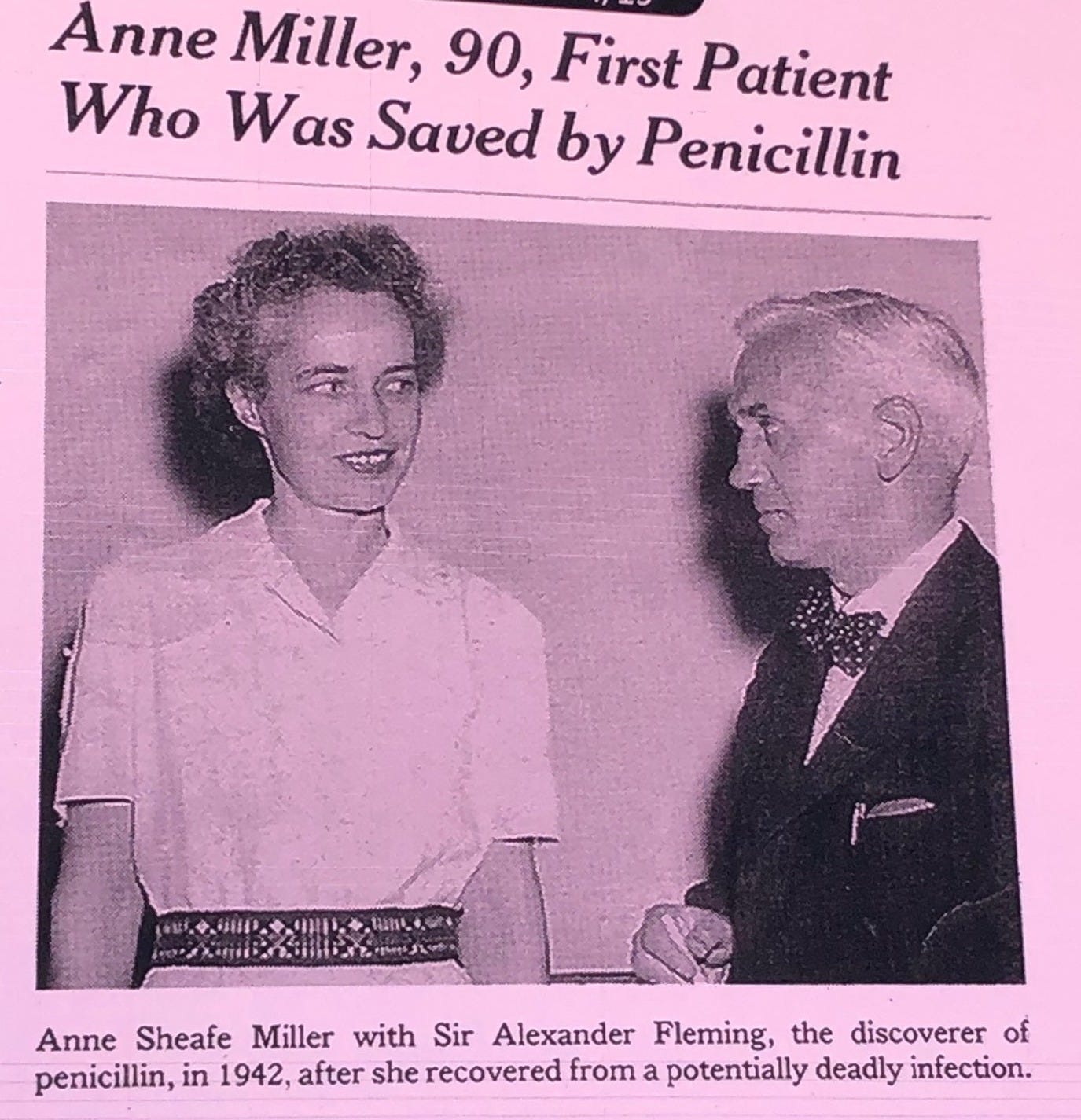

By March 14, 1942, the first American was treated with penicillin. 33-year-old Anne Miller lay near death in a Connecticut hospital, her body ravaged with a burning fever for weeks. She had developed septicemia, or blood poisoning, following a miscarriage. Doctors tried every known treatment, and in a last-ditch effort to save her life, decided to gamble on the new experimental drug. Within a day, Anne’s temperature returned to normal and she was on the road to recovery. Anne became the first American treated with penicillin. This newly developed miracle drug would ultimately save the lives of millions, including countless soldiers during WWII.

Ernst Boris Chain’s contribution cannot be overstated. He was not only a brilliant scientist — he was a proud Jew, a committed Zionist, and a man whose worldview was shaped by the ethical teachings of Judaism. Their work was not just technical; it was moral. In an extraordinary act of generosity, penicillin was made openly available worldwide without patent restrictions. This ensured rapid dissemination, mass production, and saved countless lives, exemplifying freedom not only from tyranny but from deadly disease.

By 1944, penicillin was being mass-produced and delivered to Allied forces across Europe and the Pacific.During World War II alone, penicillin is estimated to have saved at least 300,000 lives, particularly among wounded soldiers who would otherwise have died from infections. In the post-war era, studies show penicillin’s introduction led to a sharp decline in mortality from infectious diseases — for example, in Italy, penicillin reduced deaths from sensitive infections by about 58% after 1947. Ernest Boris Chain helped unlock the medical breakthrough that has saved over 200 million lives globally.

After his breakthrough on penicillin, Chain could have rested on his achievements — but instead, he applied his biochemical brilliance to entirely new fields. Ernst Boris Chain continued his scientific career with groundbreaking research in several other areas that have saved or improved millions of lives.

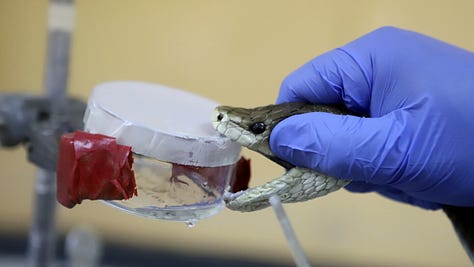

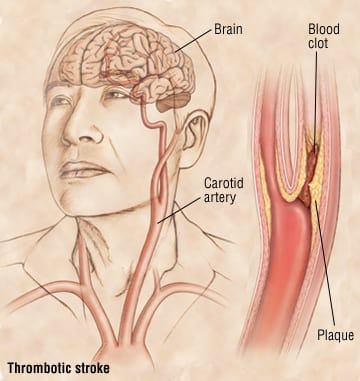

Ernst Boris Chain’s scientific contributions extended far beyond penicillin. His research into snake venoms was instrumental in advancing our understanding of blood clotting and inflammation. By analyzing the biochemical effects of venom on human physiology, Chain helped identify how certain enzymes within venoms could either accelerate or prevent clotting — insights that would later influence the development of cardiovascular drugs and lifesaving antivenoms. His work laid foundational knowledge for treating venomous bites and contributed to early research in stroke and thrombosis therapies.

In addition, Chain studied hyaluronidase, an enzyme often referred to as the “spreading factor.” This enzyme breaks down hyaluronic acid in connective tissue, enabling substances to disperse more easily through the body. Chain’s research illuminated how infections spread through tissue and also how medications could be delivered more effectively. This understanding played a critical role in shaping modern drug delivery techniques, particularly for anesthetics and antibiotics, and influenced therapies where controlled diffusion through tissue is essential.

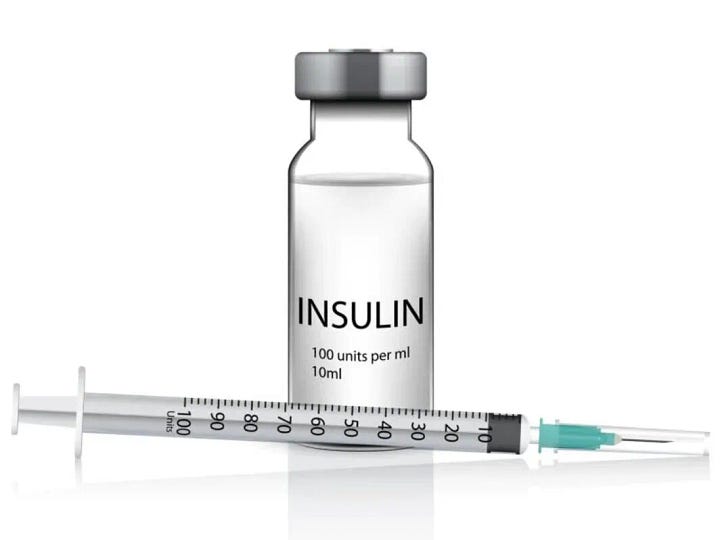

Chain also made significant contributions to our understanding of insulin, the hormone vital for managing diabetes. While not involved in its initial discovery, he helped stabilize and improve its formulation, contributing to more reliable and effective diabetes treatments. His work aided the transition from crude animal extracts to purified, controlled insulin, improving both safety and efficacy. At a time when diabetes was often fatal, Chain’s advances contributed to the development of reliable, life-saving insulin therapies that have since helped hundreds of millions of people manage the disease.

After the war, Chain also had a deep connection to Israel. He advised Israeli scientific institutions, including the Weizmann Institute, helped build its biochemistry department, and promoted Israel’s integration into the international scientific community. In 1965 he gave a speech at the Jewish World Congress, titled “Why I am a Jew.”

A new commemorative plaque now adorns the Sir Ernst Chain Building at Imperial College London, honouring one of the most influential scientific minds of the 20th century. Installed as part of the Association of Jewish Refugees’ (AJR) plaque scheme, it pays tribute to Professor Ernst Chain—Nobel laureate, refugee, and co-discoverer of penicillin—who fled Nazi Germany in 1933 and went on to revolutionize modern medicine.

When figures like Candace Owens and her peers ask, “What have Zionists ever given America?”, here is one proud Zionist, one whose contributions probably has saved her own life, at least once. Ernst Boris Chain’s life and legacy obliterates her ignorant, her hateful and ahistorical narratives. His story is only one among many, is one of resilience, brilliance, and service — not only to the Jewish people, or America, but to humanity.

Penicillin’s impact is considered one of the greatest medical breakthroughs in history, saving millions of lives both during wartime and in civilian populations ever since. Let Candace Owens and her peers be reminded of Ernst Boris Chain — a proud Jewish refugee, a Zionist, and a man whose work not only saved our soldiers from death and helped America win WWII, but has saved more lives than perhaps any other individual in modern history worldwide.

Happy 4th of July!

My mother was born in August, 1936. When she was eight years old, she contracted scarlet fever. Her parents were poor (Papaw was an alcoholic), so they desperately hoped she would recover on her own. At the last minute, they took her to the hospital where, thank God and Dr. Chain, penicillin saved her life. 🙏